What We Learned from this Year’s Landmine Monitor

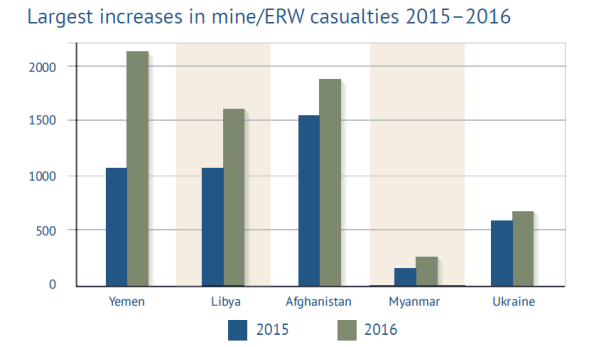

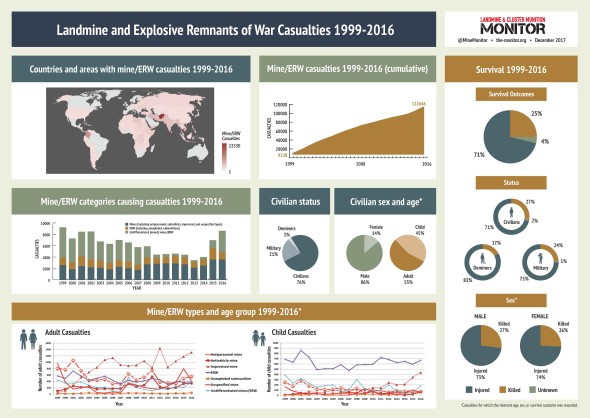

Posted: December 25, 2017 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Africa, Landmine Monitor, landmines 1 CommentSince 1999 the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor has served as the monitoring mechanism for the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty. In that time, the Monitor has documented over 100,000 casualties from landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERW) across dozens of countries. In 2016, the Monitor recorded 8,605 casualties from landmines and ERW, the highest number since the first edition of the Monitor and the most child casualties ever recorded. 2016 represents the second straight year of increased casualties after a decade and a half of decreases (The Monitor). The conflicts in Yemen, Ukraine, Libya and Syria continue to drive the increase in landmine casualties as government and rebel forces in those countries use mines as part of their war efforts. In Africa, the Boko Haram conflict has also led to increased casualties in the Lake Chad basin, along with the Islamist insurgency in Tunisia.

The Arab Spring revolution in Libya which led to the overthrow of the Gaddhafi regime also allowed for the proliferation of tens of thousands of landmines stockpiled by the regime. In the years since Gaddhafi’s death, the Islamic State gained and lost a foothold in several Libyan cities and Islamic State fighters made extensive use of mines and booby traps. In 2015, the Monitor recorded just over a thousand landmine casualties in Libya and in 2016, the Monitor recorded 1,630 casualties, or a fifth of the global total in 2016. Only Afghanistan and Yemen had more casualties than Libya in 2016.

Selected countries from the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor

Tunisia, the first country in the Arab Spring series of revolutions has experienced a long-standing Islamist insurgency in the Kasserine mountain region along the border with Algeria. The Islamists have used landmines and booby traps to protect their mountain hideouts killing and injuring both military patrols and the shepherds native to the range. In 2016, landmine casualties in Tunisia more than tripled from 2015, increasing from 20 to 65. Until 2017 when Algeria cleared the last of its minefields, Tunisia had been the only country in North Africa to declare itself landmine free, a feat reversed by the Kasserine rebels.

The Chibok girls, over 200 girls abducted from their school in northeastern Nigeria sparked the #BringBackOurGirls campaign and brought global attention to the Boko Haram insurgency. Ensconced in the Sambisa Forest of Nigeria, Boko Haram has been pushed out by a concerted effort from the allied armies of Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad and Niger which share a border in the Lake Chad basin. With the ouster of Boko Haram from their self-declared caliphate, the Islamic force has resorted to mining roads and farmlands and increasing the range of attacks into the lands of the countries aligned against Boko Haram. In 2015, the four countries had a combined 32 landmine casualties; in 2016 that figure tripled to 103 casualties, including 34 in Cameroon, a country which had previously been free of landmines.

Infographic courtesy the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor

In sum, 22 African countries had landmine and ERW casualties in 2016; of those, almost half (ten) saw a decrease in the number of victims including two countries, Burundi and Senegal, which had casualties in 2015, had none in 2016. Twelve countries saw an increase in casualties, including three, Cameroon, Guinea-Bissau and Rwanda, which recorded casualties in 2016 after having none in 2015. Somaliland had the same number of casualties in 2016 as in 2015.

There is continuing good news. In 2016 there were 2,218 landmine and ERW casualties in Africa, an increase from 2015 when there were 1,711 casualties. If we discount the increase in Libya’s casualties (626 casualties) and the increase in casualties from Boko Haram and Tunisia, the trend lines for casualties are improving. Algeria (down to 7 from 36), Mali (down to 114 from 167), Somalia (22 from 54), South Sudan (43 from 76) and Sudan (23 from 130) all saw dramatic reductions in landmine casualties from 2015 to 2016.

Michael P. Moore

moe (at) landminesinafrica (dot) org

December 25, 2017

(You keep Christmas in your way, and I’ll keep it in mine.)

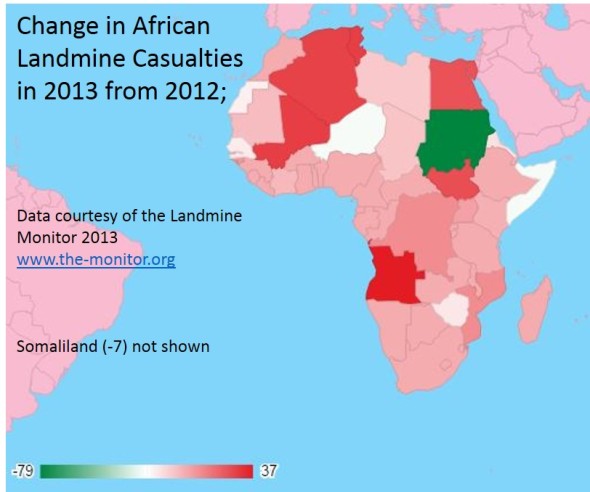

Landmine Casualties in Africa, 2013

Posted: December 9, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Africa, Landmine Monitor, landmines Leave a commentLast week, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines published its annual Landmine Monitor report, the 16th annual edition, which details the state of mine action around the world (The Monitor). One of the key findings of the report was the fact that landmine casualties in 2013 had dropped to their lowest ever recorded level: 3,308 persons killed or injured by landmines. This represented a drop of 25% in casualties from 2012 and roughly a third of the number of casualties recorded in 1999 when two people were killed or injured by landmines every hour of every day. That good news should be tempered by the constant reminders against complacency. In 2013, only 185 square kilometers were cleared of landmines (compared to 200 square kilometers in 2012) and the funding available for mine action declined by more than 10% from the record high funding of US $497 million in 2012.

In Africa, new use of landmines was reported in Libya and Tunisia; in both countries rebel groups or non-state actors were responsible. Across the continent, 647 persons were killed or injured by landmines in 2013 compared to 676 casualties in 2013, a decline of only 4% compared to the global drop of 25%. Also, ten countries (Algeria, Angola the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Mozambique, South Sudan, Tunisia and Uganda) all saw their landmine casualties increase from the previous year (The Monitor; The Monitor). Especially tragic is the increase in casualties in Mozambique which is likely to be declared landmine-free in a few months’ time and the alarming rise in Tunisia where the 28 casualties is almost triple the number recorded in the previous two decades and the first confirmed landmine casualties since 2002 (The Monitor).

Michael P. Moore

December 9, 2014

moe (at) landminesinafrica (dot) org

Landmines, Refugees and Kampala Convention on Displaced Persons

Posted: June 20, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Africa, Internally Displaced Persons, Landmine Monitor, landmines, refugees, World Refugee Day Leave a commentToday, June 20th is World Refugee Day and in recognition of the day and the threat that landmines and explosive remnants of war pose for refugees, the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor released a new report, “Landmines and Refugees: The Risks and the Responsibilities to Protect and Assist Victims.”

According to the report, “refugees or IDPs [internally displaced persons] that survive explosions, like other persons with disabilities, are among the most vulnerable groups of refugees and IDPs. They are the first who are affected physically, socially, and economically and the last to get assistance.” Also, because of “new use of landmines in Unity State, near South Sudan’s northern border, returnees have faced a myriad of hazards. In 2011, more than 200 people were killed or injured by landmines/ERW in South Sudan, most in Unity State. Many of those people were on their way back from Sudan.” The presence of landmines in the disputed Abyei region has prevented the return of thousands of displaced persons.

The report details the difficulty refugee landmine survivors face when trying to access rehabilitation services. Somali, Sudanese and Sahrawi refugees rely on limited service provision in refugee camps in Ethiopia, Kenya and Algeria and face inequalities in access to shelter, education and economic activities and live with the additional threat of sexual violence and abuse. On their return to their home countries, refugees often encounter devastated lands where meeting the basic needs of life are a challenge.

The report reminds states of their obligations to protect refugees under the United Nations Refugee Convention to which most countries are a party. The Executive Committee of the UN High Commission on Refugees called on states to “protect and assist refugees [with disabilities] and other persons with disabilities against all forms of discrimination and to provide sustainable and appropriate support in addressing all their needs…” However, the provisions of the Refugee Convention are the minimum standards and in some places, regional conventions and agreements provide for a higher standard of care and response.

In regards to Africa, there is the Kampala Convention (the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa; The Guardian; Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre), which came into force just six months ago, and is the only treaty that specifically addresses the needs and situation of internally displaced persons (IDPs) who are specifically not covered by the Refugee Convention. In Africa, there are four times as many IDPs as refugees. Among mine-affected countries, States Parties to the Convention include Chad, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Uganda and Zambia. Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Mozambique, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, Senegal, Somalia and Zimbabwe have signed but not ratified the Kampala Convention which means that they are committed to following the Convention in principle. Kenya and the Sudans have neither signed nor ratified.

Article 11 of the Kampala Convention provides for the safe return of IDPs, saying, “States Parties shall seek lasting solutions to the problem of displacement by promoting or creating satisfactory conditions for voluntary return, local integration or relocation on a sustainable basis and in circumstances of safety and dignity.” During a Brookings Institute briefing on the Convention, Chaloka Beyani, one of the drafters of the Convention, confirmed that clearing known minefields would be an obligation of States Parties since the priority of the Convention is the safe return of displaced persons. Alternatively, in places where land is abundant and if displaced persons are in agreement, relocation to known mine-free areas is acceptable which has been the practice in Angola where the low population density has allowed the country to re-settle the displaced. In either case, safe return or relocation, the Kampala Convention requires the States to assure the safety of displaced persons from landmines and other ERW.

Michael P. Moore

June 20, 2013

A Success Story in Numbers: the Improving Aftermath of Conflict

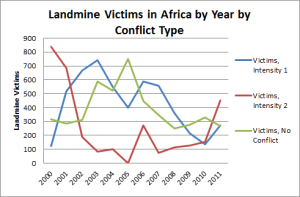

Posted: February 19, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Africa, Landmine Monitor, landmines 1 CommentWhen I started this blog, I had in mind the fear that new conflicts would lead to new use of landmines. This has been proven true in Libya (The Monitor), Sudan (IRIN News) and Mali (Agence France Presse) in just the last two years. However, the question remains as to whether this new use is part of a trend or just an anomaly? The groups using landmines in Libya, Sudan and Mali were not likely to be dissuaded from their use by international pressure or humanitarian concerns, so further investigation was warranted. Using the available data, I’ve tried to statistically review the situation.

When we talk about landmines, one of the biggest points raised is the fact that landmines and other explosive remnants of war (ERW) go on killing many years after a conflict has ended. In Egypt, landmines left over from World War II threaten the lives of Bedouins living in the battlefields of El Alamein (Al Jazeera); in Laos, ordnance dropped by American airplanes almost half a century ago prevent land from being used for agriculture (The New York Times); in Belgium a woman, not even thirty years old, is the youngest survivor of the First World War, having accidently put a bomb on top of a fire during a school camping trip (The Independent). These are very real examples, but the statistics show a definite and laudable trend: fewer and fewer people are injured every year as a result of past conflicts.

From 2005 to 2011, the number of persons killed or injured by ERW from conflicts that ended more than two years previously has dropped from almost 2,800 people to less than six hundred (see category “No Conflict” in the chart below). At the same time, the number of people killed or injured in the immediate aftermath of a conflict (“Conflict Ended”) has remained at or below one hundred persons per year (the one exception is Colombia in 2007, when the conflict in the country briefly subsided before resuming in 2009; I treat this circumstance as a statistical outlier). There are three factors playing into this: 1) because of the global stigma against their use, fewer landmines are being used, 2) humanitarian groups are getting better at reaching refugee and displaced populations with mine risk education programs, and 3) demining activities continue around the globe. I don’t dare to say which of these is the biggest contributor to the decline in landmine casualties: depending on the context and country each could be the leading factor. Another, possibly hidden, cause may be that known or suspected minefields are simply abandoned and not subject to re-use after conflicts.

On the downside, the number of landmine and ERW victims in countries in conflict has remained constant over the last several years at around 3,000 individuals per year. This number is due to the use of new landmines in countries like Pakistan, Myanmar and Colombia but also due to refugees and displaced persons fleeing conflict and traversing old mine fields in countries like Afghanistan. In these countries, the political solution of conflict termination must precede attempts to clear landmines and reduce casualty rates. However, humanitarian agencies do work in the conflict space to provide mine risk education and create safe spaces for displaced persons to gather which probably reduces the number of victims somewhat.

If we look deeper into the numbers, focusing solely on Africa, we see some of the same trends continuing and new ones emerging. In his book, Fate of Africa, Martin Meredith called the first years of the 21st Century, some of the most violent in Africa’s post-independence history. The data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program supports his assertion with 14 separate conflicts across the continent in 2000 and 2001 and 12 in 2002. However, the total number of conflict declined to a low of just five in 2005, before climbing back up to 12 in 2011.

Beginning in 2005, the number of landmine victims in conflict-free countries fell, similar to how the number of victims in all conflict-free countries fell as we saw above. In addition, the number of landmine victims per conflict declined in the same period, from almost 120 victims per conflict to about 35 victims per conflict. Except in 2011. In 2011 with the Arab Spring revolts against Libya, the renewed conflict between Sudan and South Sudan and the invasion of Somalia by Kenya to wipe out Al Shabaab, three violent (Uppsala calls them Level 2 Intensity) conflicts broke out. In these conflicts, an average of more than 150 persons were killed or injured by landmines as the total number of Africans killed or injured by landmines increased by 50% over the numbers seen in 2009 and 2010.

As I stated above, these conflicts may be unusual, but unfortunately they reverse the gains made to date. In 2000, there were six Level 2 intensity conflicts and 840 people were killed or injured by landmines in those conflicts. In 2005, there were no Level 2 intensity conflicts and a clear trend had begun where fewer and fewer landmines claimed victims in Level 1 Intensity conflicts. As the Level 2 conflicts broke out, we see a slight uptick in the number of victims per Level 1 conflict. Fortunately the number of victims in conflict-free countries continues its downward trend, a trend that, like those above, suggests when conflicts end, the number of landmine victims will gradually decrease.

Michael P. Moore

February 19, 2013

Data for this post came from the Landmine Monitor (www.the-monitor.org) and from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/UCDP/).

The Month in Mines, November 2012, by Landmines in Africa

Posted: December 11, 2012 Filed under: Month in Mines | Tags: Africa, Angola, Egypt, inhumane weapons convention, landmine, Landmine Monitor, landmines, Mine Ban Treaty, Republic of Congo, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Uganda, Western Sahara, Zimbabwe Leave a commentLandmines were both a local story and a global story in November. On the global level, the First Committee of the United Nations met to discuss disarmament issues and held its annual vote on universalization of the Mine Ban Treaty. Also in the November, the Review Conference on the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons addressed issues related to its Protocol V on Explosive Remnants of War (ERW) which includes landmines. At the end of the month, in anticipation of the 12th Meeting of States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) published the annual Landmine Monitor report, the de facto monitoring and verification mechanism for the Mine Ban Treaty. These events provided an opportunity for states and non-governmental organizations to present information about landmine issues. On a local level, landmine casualties continue to plague many nations including Somalia, Angola, Uganda and the Sudans. Positive progress was seen in Libya, the Republic of Congo and in Egypt.

Somalia

In what just may be the first time since I started compiling these monthly summaries, there were no reports of landmine casualties in Somalia. I did notice that Shabelle Media has started to use the term, “road-side bomb” more frequently in places where it used to say, “remote-controlled landmine,” but I think the change is also due to the change in the conflict in Somalia. We are seeing more grenade attacks on soft targets and assassinations than landmine attacks. This is due to the fact that Al Shabaab controls less and less territory and is not trying to defend territory; instead, Al Shabaab is trying to stoke fear through killings of journalists, leaders and random civilians. Also, the AMISOM troops are sweeping former Al Shabaab controlled areas and clearing landmines. Several have been found in the streets of Kismayo after the departure of Al Shabaab and these have been cleared, allowing for use of the roadways (All Africa).

Angola

The National Inter-sectorial De-mining and Humanitarian Assistance Commission (CNIDAH) launched a nationwide census of landmine victims as part of the strategy to create a comprehensive victim assistance plan. Previous estimates of the number of Angolan landmine survivors has been as high as 80,000 and this census will provide the first accurate estimate of the number. So far, 3,000 survivors have been identified in five provinces with another 14 to be surveyed (All Africa).

Libya

Handicap International (HI), operating in Libya since August 2011, conducted a public demolition of nine tons of ERW, representing 5,500 individual pieces of mortars, landmines, unexploded bombs and other expended and unexpended ammunition. The demolition was the result of months of collecting materials and took three hours to complete. HI has also been busy with mine risk education reaching tens of thousands of individuals with the message of the dangers of landmines and other explosive remnants of war. However, HI’s Chief of Operations in Libya, Paul McCullough, said “after eight months of EOD operations we’ve still not broken the back of the clearance” in Libya and committed to continue working until “a manageable residue is left for” Libya’s national mine action authority to complete (Libya Herald).

Mozambique and Zimbabwe

In an interview with Radio Free Europe, Guy Willoughby, a co-founder of the HALO Trust remarked that while in most countries the number of landmines is in the tens of or hundreds of thousands, “There will be a million land mines to still clear on the Zimbabwe-Mozambique border.” Both countries are working to survey the region, but the number staggers (Radio Free Europe).

Mozambique, once one of the most mine-affected countries in the world, is making remarkable progress towards becoming mine-free. To date, 97 of Mozambique’s 128 districts have been cleared or confirmed as mine-free. While the border with Zimbabwe remains to be cleared, there is hope that a project believed to require decades of work, just might be completed by March 2014 (AP Mine Ban Convention, pdf).

Congo (Brazzaville)

Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) conducted a survey of the Republic of Congo and based upon that survey has declared Congo to be free of anti-personnel mines. There had been suspected contamination around the Cabinda enclave (part of Angola that is wholly surrounded by the Congo and has been subject to a long-running rebellion). Congo requested an extension to its Article 5 mine clearance obligations (the request was submitted after the initial deadline had passed) and the NPA survey was designed to fulfill the obligations of the extension request (Norwegian People’s Aid).

South Sudan

Three children were killed and a fourth gravely injured by a landmine that was found in a swampy area in Warrap State. The incident has prompted authorities in the state to conduct more mine risk education activities to prevent future casualties (Oye! Times).

To help South Sudan build its capacity to manage the land mine threat, the Canadian Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force funded a team from South Sudan to visit the mine action authority in Afghanistan. The South Sudanese team observed mine clearance activities and had the opportunity for peer to peer learning (Norwegian People’s Aid).

As the dispute between South Sudan and Sudan over the status of the Abyei region continues, the United Nations Security Council authorized a six-month extension of its peacekeeping force there. As part of the re-authorization, the Security Council its concern about “the residual threat of landmines and explosive remnants of war in the Abyei Area, which hinders the safe return of displaced persons to their homes and safe migration” and demanded “that the Government of Sudan and the Government of South Sudan facilitate the deployment of the United Nations Mine Action Service to ensure JBVMM [Joint Border Verification and Monitoring Mechanism] freedom of movement as well as the identification and clearance of mines in the Abyei Area and SDBZ [Safe Demilitarized Border Zone].” So that settles that. It is unfortunate that demining has become politicized in the border disputes between Sudan and South Sudan, but by preventing demining in Abyei, Sudan can effectively prevent South Sudanese people from returning to the area for fear of landmines and establish new “facts on the ground” in Sudan’s favor (All Africa).

Mine risk education continues throughout South Sudan in sometimes constrained circumstances. A local NGO, the Sudan Integrated Mine Action Service (SIMAS), uses red painted stones to mark minefields instead of the formal warning signs found elsewhere. SIMAS conducts outreach to pastoral groups to inform them of the significance of the painted stones and the potential risks of entering a minefield, which all too many South Sudanese are familiar with. To date some 1.8 million people, over 20% of the country’s entire population, have received mine risk education information in South Sudan, but pastoral and traditional societies have been more difficult to reach due to their mobility and suspicions of outsiders. SIMAS has been able to earn their trust and is actively educating “children and adults in cattle camps, returnees at way stations coming back from Sudan, and other displaced persons” (UN Mission in South Sudan).

Sudan

Two boys, one 12-years old and the other 7, were injured when the landmine they had been playing with in South Kordofan State exploded. They were taken to a local hospital for treatment (Nuba Reports).

Uganda

Corruption in Uganda has become so rampant that the United Kingdom has suspended foreign aid payments amid accusations that “funds from several European countries had been funnelled into the private bank accounts of officials in prime minister Patrick Amama Mbabazi’s office” (The Guardian). Unfortunately, corruption has also affected landmine survivors in Uganda. According to the State Minister for the Elderly and Disabled, Mr Sulaiman Madada, Uganda is committed to supporting landmine victims but the funds allocated for that support were “misappropriated.” Because of corruption, survivors are unable to get prosthetic limbs or participate in economic re-integration programs. Mr. Madaba says, “We need to work together and ensure all money is used for its intended purpose.” No, Mr. Madaba. The government needs to stop stealing from its most impoverished citizens. There’s no “we” in this problem (The Daily Monitor).

Western Sahara

Two Saharawis were injured by a landmine in Smara. The landmine was likely placed by Moroccan forces who use landmines to prevent movement of the Polisario Front, the main political entity of the Saharawi people (All Africa). In London, the NGO Action on Armed Violence (AOAV), which has been working in Western Sahara for many years to provide services to landmine victims and provide mine risk education, made a presentation to the All Party Parliamentary Group on landmines. During the presentation, AOAV director, Steven Smith said “The Western Sahara is one the most heavily mined territories in the world with over 2,500 people killed in antipersonnel mine blasts” and noted the importance of providing services to landmine survivors (All Africa).

Egypt

The German, Italian and British governments have combined to provide $25 million to clear 190,000 feddans (roughly 80,000 hectares) of landmines by 2016. The area to be cleared consists of portions of the El Alamein battlefield from World War II. There are an estimated 17.2 million mines in the Western Desert where El Alamein lies, some 15% of the total number of landmines globally (All Africa).

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone’s presidential election provided an opportunity to interview members of the Sierra Leone Flying Stars Amputee Football Club. The link between the footballers and the election was tenuous, but the resilience of these young men and their efforts to overcome injury should always be celebrated (Al Jazeera).

International

In November the First Committee of the United Nations, the group of the whole which is responsible for considering disarmament issues, voted on a resolution entitled, “Implementation of the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-personnel Mines and on their Destruction.” The resolution, or one very similar, is voted on each year and is seen as a bellwether of non-states parties to the Mine Ban Treaty. This year’s resolution was approved with a vote of 152 in favor and none opposed, but 19 states abstained (no word on which states were simply out of the room at the time of the vote). Three states which abstained from the vote, Egypt, Libya and Morocco, took the opportunity to explain why they had abstained and why they also remain outside of the Mine Ban Treaty regime. These explanations can be used by the Mine Ban Treaty’s universalization advocates to address those concerns and try to get the states to accede to the Treaty. Tanzania also took advantage of the vote to promote its work and support for APOPO’s use of rats for mine clearance activities (United Nations).

The High Contracting Parties to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) met in Geneva for 6th Conference on Protocol V on ERWs, the 14th Conference on Amended Protocol II (which covers landmines and was a fore-runner to the Mine Ban Treaty), and a two-day Meeting of States Parties to the Convention. Since many countries who are not party to the Mine Ban Treaty are parties to the CCW, like Pakistan and the United States, meetings of the CCW are important opportunities for landmine advocates in NGOs and states to address issues already raised in Mine Ban Treaty meetings, like victim assistance. Rather than paraphrasing, let me quote the report on the meeting written by Katherine Prizeman of Disarmament Dialogues:

Although no “new,” groundbreaking issues related to Protocol V were highlighted or resolved this session, the continued interest and enthusiasm around its universalization and robust implementation are important for both the disarmament and human rights communities as advocates and diplomats alike work to prevent gross human suffering during acts of warfare. It is essential that HCPs, in the context of Protocol V as well as the broader CCW framework, address not only the devastating humanitarian effects of such weapons during conflict, but also post-conflict and even during times of peace. As was noted by UNMAS and other delegations, unplanned explosions of munitions and ammunition sites are increasing risks and deserve attention at all times. Damage from unplanned explosions at munitions sites is far more costly than implementation of generic preventative measures that seek to curb this threat.

Many lessons can be drawn from the work on Protocol V of the CCW, namely the central role of victim assistance, the strong emphasis placed on national reporting and corresponding national templates, and the robust and regular exchange of information and best practices in an issue-specific format. With many other related processes underway in the disarmament and human rights fields, including the ongoing arms trade treaty (ATT) process and the Programme of Action on the illicit trade in small arms and light weapons (SALWs), the hope is that CCW practices based on the values of transparency and accountability will inspire these parallel processes. Such core principles must be an inherent part of any successful arms control, disarmament, or humanitarian instrument seeking to make a concrete difference on the ground. (Global Action to Prevent War Blog).

The ICBL published the 14th edition of the Landmine Monitor covering activities in 2011 and highlighting some exciting progress on Mine Ban Treaty issues. Three states, Israel, Libya and Myanmar, used landmines in 2011, and non-state actors in six countries, Afghanistan, Colombia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Thailand and Yemen, also used mines. However, the editor of the Monitor said, “Active production of antipersonnel mines may be ongoing in as few as four countries” and no exports of landmines from those countries has been documented in several years. Therefore the number of new mines available for use is very small and existing stockpiles continue to be reduced in accordance with the Treaty. Two dozen non-state actors (rebel groups) have signed Deeds of Commitment which state that the groups will abide by the terms of the Mine Ban Treaty, further reducing the demand for landmines. The good news was tempered by the facts that the number of confirmed landmine casualties had increased slightly for the second straight year and that funding for victim assistance is at its lowest level in a decade and a full 30% less than the year before (All Africa). Also in the bad news column, Canada, the country which hosted the negotiations for the Mine Ban Treaty (which is also known as the Ottawa Treaty in recognition for where it was signed), cut its funding for mine action almost in half, from $30 million to $17 million (Ottawa Citizen).

United States

Last, AFRICOM continues to host trainings for African militaries in humanitarian mine action. The curriculum currently covers demining, ordnance identification, explosives safety and theory, metal detector operations, demolitions, physical security, stockpile classes, medical training and one-man drills, but the director of the program for AFRICOM expressed interest in adding victim assistance and mine risk education to the subject topics. As the director said, the humanitarian mine action program is “not very expensive… [and] is the most effective and has the greatest chance to build actual capacity in the country.” To participate in the training program, which has so far engaged militaries in Chad, the Republic of Congo and the Democratic Republic of Congo, nations must request support through the Department of State (AFRICOM http://www.usaraf.army.mil/NEWS/NEWS_121130_dmn.html).

Michael P. Moore

December 11, 2012

The Narrative from the 2012 Landmine Monitor; Improving or Not?

Posted: December 8, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Africa, Landmine Monitor, landmines, Mine Ban Treaty Leave a commentThe 2012 Landmine Monitor reports:

“The 4,286 new casualties from mines and ERW [explosive remnants of war] identified in 2011 are about one-third of the recorded annual casualty rate one decade ago…

“The 2011 figure is similar to the number of casualties identified in 2009 and 2010, or approximately 11-12 casualties per day. The annual incidence rate is about a third of what it was one decade ago, when there were at least 32 casualties per day. Given improvements in data collection over this period, the decrease in casualties is likely even more significant with a higher percentage of casualties now being recorded.”

The general narrative of the 2012 Landmine Monitor is one of positive improvement. From a release, “Amid the odd relapse, progress towards a world free of antipersonnel mines is inching forward” and “Some long term hold-outs [to the Treaty] have joined, namely Finland, and hopefully Poland will, too, by the end of this year. It is clear that the stigma against the use [of mines] is as strong as ever,” and “The mine action budget in 2011 was about US$662 million, the largest annual total to date” (All Africa).

In contrast, the 2011 Landmine Monitor narrative’s was not uniformly positive, mixing the positive with the negative: “Record levels of funding and mine clearance, but also increased use of landmines.”

However, in 2o11, according to the Monitor, recorded landmine victims have actually increased for the second year in the row. The Monitor explains this with the phrase “the 2011 figure is similar to… 2009 and 2010” but doens’t actually say that it is an increase. Now, there are two possible explanations: either the number of casualties has become static and the progress of the past 15 years has stalled, or the recent documented use of landmine has led to a regression and the number of casualties is slowly increasing.

First, let’s look at the possibility that the number of casualties has stabilized and the documented increases represent deviations around a new norm. The Mine Ban Treaty’s success over its first dozen years is nothing short of incredible. The fact that an accepted weapon has been given by nearly every army in the world is astounding, but if progress has stalled, surely that is an important story. The remaining holdouts to the Mine Ban Treaty, including the United States, Pakistan and China, and the countries who have not met their demining obligations within the original ten-year period are responsible for new landmine casualties. As states continue to delay on their mine clearance responsibilities and States not Party remain outside of the Treaty regime, further positive progress for the Mine Ban Treaty is not possible and so the story needs to be that the incredible progress of the Mine Ban Treaty has stalled and action by states, like the United States, is required to restart the positive momentum.

Alternatively, the fact that the number of landmine victims has increased for two years running, along with documented new use by states like Israel, Libya and Syria (and suspected use by Sudan and Yemen), actually shows that the Mine Ban Treaty regime is weakening and we can continue to see the number of victims increase. Let me offer the following in support of this: In 2009 there were 635 landmine casualties on the African continent and in 2010 there were 624, but in 2011, there were 1,009. That’s a 60% increase and can’t be explained as in line with the previous years. The new and renewed conflicts in Libya, Sudan and Somalia were responsible for most of that increase, but countries that have long been at peace like Angola, Senegal and Uganda also reported significant increases in the number of victims in 2011. The new victims in these countries are the result of failures of those states to clear their mines (especially Uganda and Senegal).

Whichever is true, the number of landmine victims is increasing or the number of victims has been stable for the last three years, neither is particularly positive. Either the great progress of the Mine Ban Treaty has stalled or worse, it has regressed. I hope it is the former and fear it is the latter.

Michael P. Moore

December 8, 2012

Items of Interest from the 2012 Landmine Monitor

Posted: December 1, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Africa, demining, Landmine Monitor, landmines, Victim Assistance Leave a commentThe Landmine Monitor, published annually by the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, is the verification mechanism for the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty. This year’s Monitor was published this week in advance of the Twelfth Meeting of States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty and has several items of interest related to landmines in Africa.

The good news reiterated the fact all of Sub-Saharan Africa is now under the Mine Ban Treaty regime after the accession to the Treaty by Somalia and South Sudan. The bad news is that the number of people killed or injured by landmines increased in Libya, Sudan and South Sudan in 2011. There’s more of each in this year’s Monitor. All quotes and references are to the 2012 Landmine Monitor, available here.

Allegations of Use of Landmines in Sudan

“In 2011, there were reports of new mine-laying in South Kordofan state in the Nuba Mountains inear the border with South Sudan as part of clashes between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the northern branch of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement / Army…(SPLM-N). [United Nations] reports claimed that both the SAF and the SPLM-N laid antipersonnel mines in strategic areas of… the capital of South Kordofan state.

“[A] British journalist… photographed three crates containing a total of at least 100… Iranian-made copies of the Israeli Mark 4 antipersonnel mine… Locals warned the journalist about entering the hill surrounding [where the crates were found], saying the area had been mined by Sudan government forces.

The government of Sudan denied the accusation, blaming the SPLM-N rebels for using the allegations of mine use as a means of gaining leverage against the government. There was no indication of whether or not the accusation of use by the SPLM-N was reviewed or refuted.

Clearing the Mines

In 2011, Nigeria declared that it had cleared all known anti-personnel landmines. This is balanced by the news that Niger and Burundi, states that were reported to be cleared of anti-personnel mines, had discovered areas contaminated with mines. In Niger, the mines are remnants from French colonial forces; in Burundi, suspected areas were reported despite previous declarations that Burundi had cleared all landmines. In total, 17 countries in Africa have mine clearance obligations that need to be met.

The Monitor reports that the extent of contamination in the Republic of Congo is unclear, however, a recent report from Norwegian People’s Aid declared the Republic of Congo free of landmines.

Uganda was due to complete its mine clearance activities in August 2012 and as of publication of the Monitor, Uganda still had work to be done.

Chad and Zimbabwe have requested initial extensions to their 10-year mine clearance obligations, extensions during which the national mine action authorities were supposed to complete surveys to determine the extent of landmine contamination and develop plans for comprehensive clearance. Neither country appears to have completed the surveys and so they are likely to require additional time beyond their estimates to complete any demining.

The Democratic Republic of Congo and Mozambique have discovered additional suspected areas of landmine contamination, but continue to make progress towards becoming mine-free according to their extension requests.

Ethiopia, seemingly alone among mine-affected countries, believes it will be able to complete demining two years ahead of schedule, provided financial resources are available.

Victims and Victim Assistance

For the second year in a row, the number of reported landmine victims increased. In 2009, a reported 3,956 people were killed or injured by landmined; in 2010, 4,191; in 2011, 4,286. The Monitor treats the increase as a consistent pattern (basically, just a minor annual fluctuation), and may simply reflect better reporting. I hope this is so.

Of the ten countries with the largest number of victims in 2011, 4 were in Africa and alone had 658 casualties, 15% of all casualties globally: South Sudan, Libya, Somalia and Sudan. In 2010, Libya reported only one landmine casualty; in 2011, Libya reported 184. In 2010, the Sudans had 149 casualties; in 2011 there were 328 casualties. These increases reflect the new reported use of mines in these countries and the continuing conflict and refugee flows.

As in previous years, children make up a large proportion, 42%, of the new casualties. In Libya, children represented 62% of the casualties and in Sudan they represented 48%.

Planning for victim assistance in Burundi, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, South Sudan and Sudan took large strides forward as they developed and implemented national victim assistance plans in compliance with the Cartegena Action Plan.

Globally, in addition to the increased number of victims in 2011, the amount of international funding dedicated to victim assistance declined by almost 30% from 2010 and is the lowest amount since records have been kept. Angola and Uganda have both closed facilities that provided services to landmine victims; support for these facilities was supposed to come from national sources, but that has not happened. This despite the fact that Angola provides more money to its own mine action program than any other country does. Angola has prioritized mine clearance over victim assistance.

Michael P. Moore

December 1, 2012

2012 Calendar of Events for Landmines in Africa

Posted: January 3, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Africa, Landmine Monitor, landmines, Mine Ban Treaty 1 Comment2012 promises to be a very busy and exciting year for mine action in Africa. The Mine Ban Treaty will come into force for the world’s newest country, South Sudan, and two nations will be expected to complete their demining obligations (Guinea-Bissau’s deadline of January 1st has already passed as of this writing). On the international calendar, we celebrate the 15th anniversary of the signing of the Mine Ban Treaty and the start of formal negotiations on an international Arms Trade Treaty after years of preparation and planning. There will be training opportunities for mine action operators and campaigns for mine ban advocates (see the ICBL’s 2012 Action Plan for a complete run-down of their priorities ).

Most of the dates below have come calendars maintained by the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) and the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery (CISR). Please let me know of any other events that should be added to this list; I will also attempt to keep it updated as the year progresses.

Events in 2012:

January 1: GUINEA-BISSAU: Article 5 demining deadline (as extended)

January 13 – February 3: UNITED STATES: “Walk without Fear” exhibition at the MAC Gallery (144 High Street, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA) hosted by Proud Students Againts Landmines and Cluster Bombs (PSALM) and the West Virginia Campaignt to Ban Landmines and Cluster Bombs (WVCBL); more info www.wvcbl.org.

March 1: INTERNATIONAL: Mine Ban Treaty 13th anniversary of Entry into Force.

March 1 – April 4: INTERNATIONAL: ICBL Global “Lend Your Leg” action

March 26 – 30: SWITZERLAND: 15th International Meeting of National Mine Action Programme Directors and UN Advisors in Geneva, Switzerland

March 31: INTERNATIONAL: Suggested deadline for States Parties to the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention with Article 5 deadlines in 2013 to submit requests for extensions.

April 4: INTERNATIONAL: International Day for Mine Awareness and Assistance in Mine Action

April 24 – 26: CROATIA: 9th International Symposium “Humanitarian Demining 2012” in Sibenik, Croatia, organized by the Croatian Mine Action Centre (CROMAC) and CROMAC-Center for Testing, Development and Training (HCR-CTRO). For more information and online registration information, visit www.ctro.hr.

April 30: INTERNATIONAL: Deadline for States Parties to the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention to submit updated transparency information (Article 7 Reports) covering calendar year 2011

May 1: SOUTH SUDAN: Mine Ban Treaty enters into force

May 7-11: SWITZERLAND: GICHD Mine Action Contracting Workshop, http://www.gichd.org/main-menu/operations/contracting-liability-and-insurance/gichd-mine-action-contracting-workshop-7-11-may-2012/, Deadline for applications is March 2, 2012.

May 21- 25: SWITZERLAND: Mine Ban Treaty intersessional meetings in Geneva, Switzerland

July 2-27: UNITED STATES: United Nations Conference on the Arms Trade Treaty: http://www.un.org/disarmament/convarms/ATTPrepCom/

August 1: UGANDA: Article 5 Demining deadline (as extended)

September – October: INTERNATIONAL: ICBL countdown to 12MSP

September 18: INTERNATIONAL: Fifteenth anniversary of the adoption of the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention

October: UNITED STATES: First Committee (disarmament) of 67th UN General Assembly in UNHQ, New York, http://www.un.org/disarmament/

November: SWITZERLAND: Convention on Conventional Weapons 5th Review Conference in Geneva, Switzerland

December 3: INTERNATIONAL: 15th Anniversary of signing of the Mine Ban Treaty

December 3 – 7: SWITZERLAND: Mine Ban treaty 12MSP in Geneva, Switzerland

Michael P. Moore, January 3, 2012

The Month in Mines: Landmines in Africa in November 2011

Posted: December 1, 2011 Filed under: Month in Mines | Tags: 11MSP, Africa, landmine, Landmine Monitor, Libya, Mine Ban Treaty, Somalia, South Sudan Leave a commentNovember saw the publication of the 2011 edition of The Landmine Monitor and the opening of the Eleventh Meeting of States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty (11MSP) in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. These two events help to remind the global community of the continuing threat that landmines pose and the reports of new usage of mines in Libya (and elsewhere) was a major theme to coverage of these events (BBC News). With news stories also covering landmine-related incidents and events in Sudan, South Sudan, Rwanda, Burundi, Angola and Somalia, let’s start this month’s wrap-up on the positive side of the ledger.

The Good News:

South Sudan became the 158th state to ratify or accede to the Mine Ban Treaty in mid-November (All Africa). Since the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement that ended the civil war in Sudan and established the process for South Sudan to emerge as an independent state in July of this year, demining, risk education and victim assistance activities have been conducted in South Sudan, all 10 of whose states are considered mine-affected. Acceding to the Mine Ban Treaty was South Sudan’s first international treaty action as an independent state.

On the first day of the 11MSP, Burundi declared itself to be free of anti-personnel landmines. Remarkable for a country that faces significant economic and political challenges, Burundi has been able to achieve this milestone a full three years prior to the Treaty-mandated deadline for mine clearance (Monsters and Critics).

Rwanda conducted a stockpile destruction exercise in conjunction with the Regional Centre on Small Arms, destroying over 40 tonnes of ammunition that had been recovered from rebel groups and from old stockpiles held by the Rwanda Defense Forces. The exact composition of the stockpile to be destroyed was not clear, but the act represented a continued effort by the Rwandan government and military to eliminate unexploded ordnance and explosive remnants of war. In past exercises, Rwanda had destroyed over 1,000 landmines (All Africa).

In Angola, demining activities continue apace and Mines Advisory Group (MAG) reported on an effort to re-open schools in Moxico province, schools that had been closed due to the presence of landmines on school grounds. By clearing 248,000 square meters of land and working with donors, MAG reports that construction of a new school will be completed before the end of the year and the teachers will receive special training in mine risk education to help ensure the safety of their pupils (Alert Net).

The Landmine Monitor reported 615 landmine casualties in Africa in 2010, a slight drop from 2009’s estimate of 629 casualties, although globally the casualty figures were up 5% in 2010 from 2009 (The Monitor). This continued the general trend of the last decade with landmine casualties decreasing nearly every year. Also in 2010, international funding for mine action was its highest ever and greatest amount of land was cleared ever (Voice of America). Unfortunately, the good news ends there…

The Bad News:

For the first time since 2004, the number of countries using landmines increased, including Gaddhafi’s regime in Libya (The Monitor). New usage of mines is also suspected in South Sudan and Somalia, but has not been confirmed officially by The Monitor.

In South Sudan’s oil-rich Unity state, a war is brewing. Rebel groups in the areas appear to be using landmines, especially anti-vehicle mines, to disrupt traffic and oil extraction activities. New mines have also been placed around the disputed territory of Abyei. Unfortunately the presence of these new mines has only been revealed by catastrophic accidents such as the October 9th incident when 20 people aboard a bus in Unity were killed by an anti-tank mine and the August 4th incident when 4 peacekeepers were also killed by an anti-tank mine (All Africa).

As mines continue to be laid, two of the most vulnerable populations are refugees moving through the newly mine-affected area and refugees returning to their home areas. Newly mined areas won’t be marked and refugees lack the recent knowledge to know where potential minefields might lie. A second nascent conflict is emerging in Sudan’s South Kordofan state, just north of Unity state. The Sudanese army has shelled villages in South Kordofan driving refugees across the border into Unity state where the new minefields threaten refugees. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees is trying to relocate a refugee camp in Yida in Unity state where hundreds of South Kordofan refugees have sought security (All Africa). The rebel group in Unity state, South Sudan Liberating Army, has announce a planned offensive for December, allowing enough time for the refugees in Yida to be moved (All Africa).

Prior to July, South Sudan was on target to complete demining of its territory by 2014. However, the new use of landmines means that at least six more years (until 2017) will be needed to complete the demining, a deadline that could get pushed further back as rebels continue to mine roads, sometimes within hours of their clearance by international and domestic operators. The hospitals in South Sudan, despite the nascent state having a comprehensive victim assistance policy, are not up to the task of comprehensive rehabilitation of landmine survivors (Voice of America).

In Somalia, the impact of Kenya’s invasion and Ethiopia’s encroachment has been to cause the Al Shabab rebels to switch their tactics. Whereas before Al Shabab would operate in the open (having no real resistance in the country before Kenya’s incursion), now Al Shabab is pursuing a dedicated insurgency campaign that relies on improvised explosive devices and landmines. Two towns near the Kenya-Somalia border, Garissa and Mandera, have been the sight of several grenade and landmine attacks that have been attributed to Al Shabab (All Africa) (All Africa) (All Africa) (All Africa) (All Africa). Garissa and Mandera are the nearest towns to Dabaab refugee camp where thousands of Somalis sought refuge after the summer’s famine.

In addition to the attacks on Kenyan soil, Al Shabab continues to operate in Mogadishu with October and November seeing the greatest number of casualties from landmines and IEDs. Ten people were killed by landmines in the last four days of November alone in at least three different incidents (Press TV) (All Africa). Another incident occurred at a main crossroad in the Bakara market (Americans will remember Bakara market as the site of the Black Hawk Down events), when a buried landmine killed at least four people (Mareeg).

These new use of mines in South Sudan and Somalia almost certainly mean that landmine casualties in these two countries will be higher in 2011 than in 2010, and they were already the African countries with the most casualties – 82 in South Sudan, 159 in Somalia – in 2010.

In Libya, the long process of demining is just beginning. The international community continues to be focused on shoulder-fired rockets (known as MANPADS) and the threat to airline travel posed by such rockets (All Africa), but the real focus should be on the ground, not in the skies. Dozens of Libyans have been killed or injured handling unexploded ordnance (UXO) and Libyan Red Crescent volunteers have been trained in mine risk education techniques to spread the word about the dangers of landmines, grenades, mortar shells and cluster munitions (Geneva Lunch). The Joint Mine Action Coordination Team (JMACT) in Libya hosted Georg Charpentier, the United Nations Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Libya, on a tour of mine and UXO-affected areas in Misrata (JMACT), and Mr. Charpentier responded by calling for more support for mine clearance activities (United Nations). Here’s hoping Mr. Charpentier’s words are heeded.

Michael P. Moore, December 1, 2011.

Findings from the 2011 Landmine Monitor for Africa

Posted: November 29, 2011 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: 11MSP, Africa, landmine, Landmine Monitor, Mine Ban Treaty Leave a commentThis week, the Eleventh Meeting of States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty (11MSP) is being held in Phnom Penh, Cambodia and last week, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines released the 2011 edition of the Landmine Monitor (The Monitor). These two events create an opportunity to review recent news in the mine action community.

There has been some good news. In one of the first announcements at the 11MSP Burundi declared itself to be landmine-free (Monsters and Critics). South Sudan acceded to the Mine Ban Treaty as its first major interaction with the international community (The Monitor). The Monitor reported that in 2010, the total number of persons killed or injured by landmines in Africa had declined from 629 to 615 with more than half of the mine-affected states on the continent reporting fewer casualties than the previous year. That good news has been over-shadowed by the bad news. More casualties were reported in seven mine-affected states (Angola, Eritrea, Mozambique, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan) in 2010 than in 2009. New landmine usage has been reported as conflicts broke out or escalated in Libya, South Sudan and Somalia meaning that landmine casualties can be expected to increase in 2011 from 2010. Despite the fact that for the first time in four years new countries (Finland, South Sudan and Tuvalu) have acceded to the Mine Ban Treaty, global landmine use is higher than it has been since 2004 (The Monitor).

Only one state in Sub-Saharan Africa, Somalia, remains outside the Mine Ban Treaty, whilst three North African states, Egypt, Libya and Morocco, have failed to accede to the Treaty; all four countries maintain stockpiles of anti-personnel mines.

Nigeria declared itself to be landmine-free, the 18th state to do so globally, joining Gambia, Malawi, Rwanda, Swaziland, Tunisia and Zambia as landmine-free African states.

Angola and Chad have more than 100 square kilometers contaminated by landmines and the unofficial regions of Western Sahara and Somaliland are also mine-affected.

Sudan, Angola and Mozambique cleared more than 13 square-kilometers of mine-affected areas in 2010, an increase over 2009’s 12 square-kilometers.

Algeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Eritrea and the Republic of Congo have all submitted requests for extensions of their demining obligation deadlines. Of the African states that have already received deadline extensions for demining, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania and Mozambique are on-track to meet their new deadlines; Senegal, Uganda and Zimbabwe are all falling behind on their schedules and Chad’s progress is unclear.

Angola, Chad and DRC conducted nationwide assessments of victim assistance needs as part of the process of drafting a national victim assistance plan. Uganda, DRC, Mozambique and South Sudan have developed (with various degrees of approval and implementation) national victim assistance plans and Burundi and Chad have begun the process of drafting plans.

20 African states received more than $100,000 in international contributions in 2010 for mine action assistance. Angola was the largest African recipient, receiving $45.7 million in 2010, Sudan was next with $27 million and DRC was 3rd with $13.2 million. These three nations were the only African states in the top ten recipients globally, a chart easily topped by Afghanistan which received $102.6 million. Only 9% of all mine-action assistance globally went to funding victim assistance (The Monitor).

Michael P. Moore, November 29, 2011.