Landmines are not the solution to any border problem

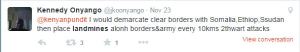

Posted: November 24, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Borders, China, Finland, India, Kenya, landmines, Mexico, Russia, Somalia, Ukraine, United States Leave a commentI monitor Twitter on a daily basis for news about landmines. In the wake of Saturday’s massacre of 28 people riding a Nairboi-bound bus near the Kenyan border town of Mandera by members of the Al Shabaab militia (Reuters), I saw several posts on Twitter suggesting radical measures to close the border between Somalia and Kenya:

The anger of the writers and posters is understandable: many of their fellow Kenyans have been killed by a militia that is based in another country. The use of landmines to secure the border is an easy-sounding solution, but one that will result in many more civilian casualties and not protect Kenyans. As examples, the French and Rhodesian governments placed “cordon sanitaires” on the borders which, despite multiple layers of minefields, barbed-wire, machine gun emplacements and electronic monitoring, completely failed to prevent incursions by rebel groups which seized power in Algeria and Zimbabwe. Two modern minefields, on the Korean Peninsula and in Western Sahara, also fail to prevent people from crossing the borders or provide a lasting solution to the conflict between the peoples on either side.

Kenyans are not the only ones to suggest using landmines to protect borders. Others I have seen recently include Indians:

Finns:

Ukrainians:

And Americans:

I doubt that those recommending the use of landmines are representative of their fellow citizens, but I do find it troubling to see any proposals to secure borders with landmines. Landmines are not the solution to any border issue. Civilians are inevitably the victims of these minefields and if anything, active minefields harden the conflict and make finding a permanent resolution more difficult (again, see Korea and Western Sahara). Fences and minefields do not make good neighbors. Communication and understanding make good neighbors while minefields make enemies.

Michael P. Moore

November 24, 2014

Moe (at) landminesinafrica (dot) org

The Month in Mines, October 2014

Posted: November 20, 2014 Filed under: Month in Mines | Tags: Africa, Algeria, Angola, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Kenya, landmines, Libya, Mali, Namibia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, Western Sahara Leave a commentLandmines have been called weapons of mass destruction in slow motion. This month’s stories, which report on casualties from landmines laid 70 years ago as well as just a few weeks ago, prove that adage. While heroic efforts are ongoing to clear the landmine contamination, emerging and continuing conflicts provide ample opportunity for new use.

Somalia

As the Somali National Army (SNA) and various regional militias, supported by the peacekeeping (peacemaking?) forces of the African Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), engage in a new offensive against Al Shabaab, we can expect to see reports of landmine use and asymmetrical warfare. In the Galgala mountain range of the semi-autonomous Puntland state, Puntland forces “flushed” Al Shabaab from the mountains that had been their base for several years. To defend their base, Al Shabaab had laid mines which killed one Puntland officer and injured two others (All Africa). In southern Somalia, an armored vehicle stuck a landmine outside of Kismayo; no injuries were reported (All Africa). And in the Shabelle region in the middle of Somalia, near the Ethiopian border, AMISOM forces struck a landmine in Marka town which resulted in at least a dozen civilian injuries and an unknown number of military casualties (Codka 24).

In addition to the military actions, a court sentenced a suspected Al Shabaab member to death for a plot to place a landmine in the Puntland town of Bosaso (Horseed Media).

Angola

Norwegian People’s Aid provided landmine clearance and detection training to 35 members of the Angolan army in Zaire province where some 6 million square meters of land need to be cleared (All Africa). In the first half of 2014, some 33,000 pieces of unexploded ordnance, including anti-personnel landmines, have been found and cleared in Zaire Province (All Africa). In Cunene Province, almost 350,000 square meters of land was cleared in 2013 by the National Demining Institute and in 2015, the Institute plans to clear another 10,000 hectares to enable expanded agricultural outputs (All Africa). In the central Bie Province, 174,000 square meters have been cleared of landmines over the last twelve months (All Africa).

Mali

Mali continues to see new use of landmines in the restive northern region where Islamists had briefly declared a caliphate before being dislodged by French forces. According to some sources, Islamists are paying US $200 to youths, who may or may not even be Muslim, who place landmines in the roadways used by the UN peacekeeping force, MINUSMA, in northern Mali. A bonus of US $1,000 is paid if a mine kills a French soldier (Le Monde). The MNLA, a Tuareg group that had sided with the Islamists and is now closer to joining the government’s coalition, had two members seriously injured by a landmine, when the vehicle they were riding is struck a mine near the northern city of Kidal (MNLA). Three Senegalese peacekeepers with MINUSMA were injured by a landmine also near Kidal; two were injured severely and transported to Dakar for treatment (Reuters).

Western Sahara

The Sahrawi Ambassador to Algeria reported that Morocco had planted more than 5 million anti-personnel landmines and an unspecified number of anti-vehicle mines in the Western Sahara region while speaking at the opening of a photo exhibit of landmine clearance. The ambassador called on Morocco to assist in the clearance efforts (All Africa).

Tunisia

While the one lingering bright spot from the Arab Spring revolutions, Tunisia continues to struggle with its own Islamist insurgency based in the mountain ranges along the border with Algeria. The Tunisian military has been actively engaged in the conflict, but has not been able to defeat the rebels. Seven soldiers were injured by landmines in two separate incidents in the Sakiet Sidi Youssef area of Kef (All Africa; Cihan News Agency). In later reports from the military, a landmine explosion was acknowledged but no casualties were reported from the blast (All Africa).

Libya

The civil war in Libya (and to be honest, it’s probably multiple wars) has shifted focus away from Tripoli to Benghazi, the heart of the original uprising that toppled the Gaddhafi regime. As forces aligned with the internationally recognized government advanced on Benghazi, airstrikes and street to street fighting erupted. A soldier with the Libyan army was killed trying to defuse a landmine; unclear if the mine was newly laid or dated from the 2011 conflict or even earlier (All Africa).

Egypt

In Sinai, where an insurgency has rumbled along since Mohamed Morsi’s ouster, a child was killed by a landmine that was a suspected remnant from earlier wars (Arab Today). Also in Sinai, two women were injured by an anti-tank landmine near the border with Gaza (TNN). Despite these incidents and others in recent years, it is the minefields in western Egypt which date back to the tank battles of World War II that receive all of the attention and have caused the majority of casualties. A World War II landmine near the Libyan border injured eight Egyptians who were trying to cross into Libya seeking work (Ahram). The European Union allocated 4.7 million euros to support demining efforts in the western desert to support the government’s longstanding development plans for the region (All Africa). All told, there were more than 22 million landmines in Egypt, 17.5 million in the western desert and 5.5 million in Sinai; the Egyptian government has cleared 1.2 million mines over the last two decades (a rate which would mean that another two centuries are needed to clear the rest of the mines). In the last 15 years, over 8,000 people have been killed or injured by landmines making expedited clearance a necessity (Ahram).

Namibia

Namibia has declared itself free of all known landmines, but the construction of a 200 kilometer highways faced some delays due to the suspected presence of unexploded ordnance in the right of way. This was a reminder that even if a country has completed its demining for anti-personnel landmines under the Mine Ban Treaty, the danger of unexploded ordnance of other types may remain (New Era).

Central African Republic

Sticking with countries we don’t mention too often in these pages, the Central African Republic will soon see an engineering contingent of Cambodian peacekeepers in the country. Among the Cambodians’ tasks will be demining which, as in Namibia, will likely focus on unexploded ordnance as there have been no reports of landmine use in the Republic despite the violence of the last couple years (and the many, many years previously) (First Post).

Kenya

Kenya is also not a mine-affected country, but does have several military installations which have not been adequately marked and cleared. These installations include firing ranges where explosive ordnance was used to practice and when four herders passed through old ranges, one of them stepped on an unexploded piece of ordnance, causing it to explode and injuring all four (Baringo County-News).

Algeria

With around 11 million landmines dating from World War II, the liberation war with the French and the civil war of the 1990s, Algeria was once one of the most mine-affected countries in the world. With up to 80,000 killed or injured by mines, Algeria has made massive efforts to address the problem, clearing 8 million mines as of 2000. Clearance operations were halted from the early 1990s until 2004 when demining resumed in earnest. Algeria anticipates meeting its Mine Ban Treaty deadline of clearing all anti-personnel mines by 2017 (Qantara). Algeria continues to make steady progress towards mine clearance with over 3,600 mines cleared in September alone by Algerian army units (All Africa). In the decade since demining resumed, almost 1 million mines have been cleared which would leave an estimate 2 million mines yet to be cleared (Arab Today).

Sudan

Two Darfurian children died from alleged poisoning after touching a bomb dropped by the Sudanese Air Force near Jebel Marra. After picking up the bomb, they ate their dinner and died within half an hour of eating from vomiting and diarrhea. Other local reports suggest that livestock in the area suffer from paralysis, diarrhea and skin rashes. “The people in East Jebel Marra believe that the bombing by the Sudanese government has poisoned the drinking water, affecting the livestock” (Radio Dabanga). These allegations should be followed up on to determine the true causes of the deaths of these children and livestock. Poisoning of water or delivery of poisonous substances by bombing would represent egregious violations of human rights.

South Sudan

The Development Initiative (TDI) has launched a few new projects in South Sudan in partnership with the United Nations Mine Action Service. The projects include technical survey and landmine clearance and will provide emergency as well as long-term clearance capacity (TDI).

Democratic Republic of Congo

Of the more than twenty rebel groups to emerge and try to overthrow the Ugandan government since Yoweri Museveni seized power in 1986, one of the more obscure yet frightening is the Allied Democratic (or occasionally “Defence”) Front (ADF). From a base in the Rwenzori Mountains in western Uganda and eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the ADF launched several daring raids in the late 1990s on police and military positions in western Uganda as well as an assault on a school in which students were abducted and forced to serve as child soldiers for the ADF. The ADF used mines to disrupt travel on the roadways and was subsequently defeated by the Ugandan army in a brief campaign linked to Uganda’s other adventures in the DRC. In very recent days, the ADF has re-emerged in the DRC where it is manufacturing its own landmines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) following designs used by Al Shabaab in Somalia. The ADF had been supported in the 1990’s by the government of Sudan in Khartoum as a proxy force against the government of Uganda (which was supporting rebels in South Sudan against Khartoum) and many of the ADF’s members were radical Islamists which is the link to Al Shabaab. In its current incarnation, the ADF’s mines and IEDs are taking a toll on the United Nations’ Force Intervention Brigade which had been deployed against the Congolese militia M23 and similar groups. It’s not clear how many people have been injured by ADF’s mines, but the attacks appear to have started in January 2014 (African Armed Forces).

Michael P. Moore

November 20, 2014

moe (at) landminesinafrica (dot) org

When language gets in the way of good news: Is Zambia “landmine-free”?

Posted: November 17, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: landmines, Mine Ban Treaty, Zambia 1 CommentIn recent months, we’ve discussed Zambia and noted that there appears to be confusion over whether or not there are any landmines in Zambia. Recently I had the opportunity to speak with Bob Mtonga, a Zambian physician and disarmament advocate, and he explained to me the situation which is this: to the best of anyone’s knowledge, all known landmines have been cleared from Zambia. However, because landmine use in Zambia was “nuisance” mining without any specific pattern, there remains the possibility that previously unknown and undocumented landmines could be found in Zambia. This possibility prevents the Zambian government from making any statements, definitive or otherwise, about whether or not Zambia is landmine-free. Which is understandable. If Zambian officials declared the country landmine-free and someone where to discover or be injured by a mine, then the credibility of the government and the landmine clearance process could be called into question.

However, the government’s equivocation on the subject and silence when asked directly leads to fears that the country still has a landmine problem. Already, in response to the uncertainty, the British government has revised its travel advice for Zambia which could impact tourism in the country. So, what can a country do in this situation? And, can a country ever announce that it is truly landmine-free?

To be clear, there is no reason to believe that there are any landmines in Zambia. There have been no confirmed reports of landmine incidents for five years and the government maintains an explosive ordnance disposal unit to respond to any potential issues. But what Zambia’s situation shows is the problem with how we talk about landmine clearance and what it means to be “landmine free.”

Allowing my inner lawyer out, there are really three standards that can be applied to a country: “landmine-free,” “landmine impact free,” and “compliant with Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty.” “Landmine-free” means just that: there are absolutely no landmines in a given area, usually a country. It is an absolute and probably only reflects countries in which landmines have never been used. It also encompasses all landmines, anti-personnel and anti-vehicle. “Landmine impact free” and “compliant with Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty” have very specific definitions which may or may not meet the absolute standard of “landmine-free.”

Compliance with Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty means that all known anti-personnel landmines have been cleared from a country. A country can still have known anti-vehicle mine contamination and be compliant with the Article 5 because the Mine Ban Treaty’s obligations are specific to anti-personnel landmines. Compliance only affects the 162 countries party to the Mine Ban Treaty.

Landmine impact free (as defined in the International Mine Action Standards) can mean that a country may still have landmines, anti-personnel or anti-vehicle, but such mines do not have a negative socio-economic effect on communities. Countries not party to the Mine Ban Treaty can (and often do) aspire to being landmine impact free.

“Compliant with Article 5” and “landmine impact free” are both time-specific descriptions. Because compliance with Article 5 means only known landmines are cleared, a country that has previously declared itself compliant with Article 5 can identify previously-unknown minefields and still be compliant. This happened in Burundi and Germany and the governments then proceeded to clear the newly discovered minefields. Because landmine impact free refers to the absence of negative socio-economic effects on communities, there is the possibility that changes in a community would change the effect existing landmines have on that community. For example, a particular community could exist for some time next to a marked and known minefield but when that community grows in population and begins to need additional agricultural land to support itself, the community might encroach upon the minefield because there is no other available land for farming. By definition, a country that has completed landmine clearance under Article 5 is landmine impact free.

So where does that mean for Zambia? Zambia is in compliance with Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty. Zambia is landmine impact free. Is Zambia absolutely landmine free? Maybe, maybe not; but Zambia should be proud of clearing all known landmines and fulfilling its obligations under the Mine Ban Treaty and should not be silent about it. Zambia’s foreign minister Harry Chiluba has been traveling throughout the country to reassure Zambians that there are no known landmine dangers in the country and that should any threats be discovered, the government will respond swiftly and fulfill its obligations to survivors and victims of mines. Thus, Zambia is doing everything it can to live up to the aspiration of being landmine free.

Michael P. Moore

November 17, 2014

moe (at) landminesinafrica (dot) org

OT: Consider Band-Aid as a Gateway Drug

Posted: November 14, 2014 Filed under: Off-Topic | Tags: Band Aid, Bob Geldof, Ebola Leave a commentSmall confession: I like “Do they know it’s Christmas?” and will probably buy the Band-Aid 30 single. It’s a decent pop song with a few good hooks and the Band-Aid 25 version wisely ditched the synthesizers for electric guitars. As a depiction of Africa, it’s so laughably false as to stagger the imagination. Lines like “Tonight, thank god it’s them and not you;” “Where the only water flowing, is the bitter sting of tears;” and the repeated “Feed the world” are massive failures of fact but reflect Bob Geldof’s bombast and the simple point he was trying to make in 1984: “Give us your fucking money!”

Since Bob Geldof announced Band-Aid 30, I’ve seen a lot of commentary about how the song is dated, it contributes to a false stereotype of Africa and Africans, it takes away from other charitable ventures, Geldof’s a smug bastard whose just trying to stay relevant, et cetera. And this is all very true. But it should not take away from the fact that money raised by Band-Aid 30 will do some good and the awareness-raising that goes along with the single will do much more.

Band-Aid 30 might, might raise US $10 million. The United States government has discussed allocating $6 billion. But Band-Aid does two things the US government cannot: 1) it gets people to contribute to global development challenges who would otherwise not do so, and 2) it’s a gateway drug for future development professionals.

Bob Geldof is not a dumb man. He knows the lyrics aren’t true, but this is the fourth release of the single and each time he’s released it, the song has topped the British music charts and raised money and awareness for what are fairly complex issues like politically-engineered famines and multilateral debt relief. Band-Aid also gives people a simple answer to the age-old question of “What can ordinary people do about extraordinary problems?” Simple: buy the record (or probably MP3 file or iTunes single these days) and feel good about yourself. People who do not otherwise give to global charities will buy the Band-Aid 30 single and those dollars will go to fight Ebola. That’s a pretty good outcome. Is it as good as giving directly to Doctors without Borders or Samaritan’s Purse or the other organizations on the ground in West Africa right now? No. But my guess is the people who buy Band-Aid 30 weren’t going to give money to those organizations. So if the option is not giving anything to fight Ebola and buying Band-Aid 30, then Band-Aid 30 is the preferable option.

But what Band-Aid 30 will also do is also engage people. How many people will read about the US’s contribution? Not many. How many will buy the Band-Aid single? Many, many more. Some of the people who buy or listen to the single will want to learn more about Ebola and the health systems in West Africa. Will this be a large number? No. But these will become the people who support the MSFs of the world. I clearly remember listening to Band-Aid and Live Aid in 1984 and 1985 and that sparked a lifelong interest in international development. My guess is there are many other development professionals for whom Band-Aid was their gateway drug to global issues. People need to start somewhere and Band-Aid is an invitation to do so. People who buy the single will watch the documentaries and the news reporting with a little more interest and care and learn about the realities of the situation.

So it’s okay to buy the Band-Aid 30 single; but also send MSF a much bigger donation…

Michael P. Moore

November 14, 2014

moe (at) landminesinafrica (dot) org

Sliding Backwards: Landmine use in Libya

Posted: November 5, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: landmines, Libya 1 CommentToday’s report from Human Rights Watch confirms that militias fighting over the Tripoli Airport in Libya used anti-personnel and anti-vehicle landmines. HRW’s report affirms the claims made on social media after the July and August battles when the Libyan Dawn militia ousted the Operation Dignity militia from the airport and Tripoli (Landmines in Africa; Landmines in Africa). In terms of loose alliances, Libyan Dawn is associated with Islamist forces from Misrata while Operation Dignity is led by former Libyan general Khalifa Haftar and is supported by the internationally-recognized government of Libya, which is now based in Tobruk, hundreds of miles from Tripoli near the Egyptian border. Operation Dignity also has the support of elements of the official Libyan army. The Libyan Dawn militia is composed of many of the militias that ousted the Gaddhafi regime in 2011 (Oxford Analytica; Al Arabiya; Middle East Eye). Those militias pledged not to use landmines of any sort in 2011 after the Gaddhafi regime used them widely in his failed bid to keep power (Human Rights Watch) and in the months that followed Gaddhafi’s overthrow, significant progress was made to clear some of the mines in the country (Human Rights Watch). HRW’s report shows that the good work may be unraveling. The continuing and spreading conflict in Libya means new landmine contamination might not be isolated to the Tripoli airport.

As the battle for Benghazi continues in eastern Libya, the Operation Dignity forces appear to have the upper hand. Just as in the battle for Tripoli, reports are emerging about landmine use in Benghazi by the militias. The Libyan army cleared landmines from Sidi Mansour, east of Benghazi as it pushed Libyan Dawn forces from the city. At least one Libyan soldier was killed while trying to dismantle a landmine (Magharebia). If true, this would suggest that the militias which had pledged to not use landmines against Gaddhafi have reneged on that pledge in their fight against Haftar and Operation Dignity.

Libya has many, many landmines already. All combatants and militias in the country should abandon the use of these weapons.

Michael P. Moore

Moe (at) landminesinafrica (dot) org

November 5, 2014

The Imperative to Ban Anti-Vehicle Landmines

Posted: November 3, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: CCW, landmines, Mine Ban Treaty, MOTAPM Leave a commentAnti-personnel landmines are specifically banned by the Mine Ban Treaty, which 162 countries have agreed to be bound by, and regulated by Amended Protocol II of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, which key Mine Ban Treaty hold-outs China, India, Pakistan, Russia and the United States are party to. The dramatic reduction in casualties from anti-personnel landmines is largely due to these two treaties which were negotiated and came into force in the late 1990s. However, both treaties specifically avoided regulation or restriction on the production, transfer and use of anti-vehicle (or anti-tank) landmines. As a result, anti-vehicle landmines probably present a greater humanitarian threat than anti-personnel landmines.

Over the last decade or so, a group of countries, led in large part by the United States, has pushed for a new protocol for the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) that would specifically address the humanitarian impact of anti-vehicle mines, or “mines other than anti-personnel mines” (MOTAPM) as they are referred to in the CCW. Recently, the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) and the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) published a report on the humanitarian and development impact of anti-vehicle mines. The report compiled existing research conducted by the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and added in three country case studies to demonstrate the findings reported by the ICBL and the ICRC. The report showed that the impact of anti-vehicle mines may actually be increasing as post conflict countries like Cambodia develop as well as the fact that new mine usage in South Sudan appears to be entirely anti-vehicle mines. The report recommended regulating the use of anti-vehicle mines to reduce their humanitarian impact and regulating the production of the mines to ensure detectability.

As of today, the only restriction on the production of anti-vehicle is that they cannot be designed so as to detonate in the presence of a metal detector or similar mine detection equipment. The only regulations on their use is they cannot be used “indiscriminately” or to deliberately target civilians. There are no regulations on their transfer, except those imposed by individual nations (e.g., the US will not export any “persistent” anti-vehicle mines). Since 1997, anti-personnel mines have been required to contain a certain amount of metal to ensure detectability by metal detectors or similar devices; anti-vehicle mines have no such requirement. The Arms Trade Treaty, when it comes into force later this year, will restrict transfer of anti-vehicle mines (and a host of other military equipment and items) to countries in conflict or where gross violations of human rights, including gender-based violence, are occurring. That’s a good start, but the damage has been done.

When the Gaddhafi regime in Libya fell, hundreds of thousands of stockpiled anti-vehicle mines were looted by various militias. Other countries, like the Central African Republic, which had eliminated their stockpiles of anti-personnel landmines in accordance with the Mine Ban Treaty have been revealed to have stockpiles of anti-vehicle mines. In South Sudan and Mali, humanitarian relief is hampered by the presence of newly laid anti-vehicle mines in roadways. But it’s the old anti-vehicle mines that really demonstrate the horror of these weapons. Earlier this year, in Guinea-Bissau which has cleared all of its anti-personnel landmines, a minibus struck an anti-vehicle mine that had been laid three or four decades earlier killing 22 people. In Egypt, the western desert is polluted with millions on anti-vehicle mines left over from the tank battles of World War II; less than a week ago, eight Egyptians were injured by one such mine. In Cambodia, as the country develops and tractors are introduced to improve agricultural output, farmers are finding anti-vehicle mines in areas that were known to be free of anti-personnel mines, often with tragic consequences.

The success of the Mine Ban Treaty has meant that the number of people injured and killed by anti-personnel landmines. But as we see in places like Angola, where deminers find one anti-vehicle mine for every 15 to 20 anti-personnel landmines, the number of incidents involving death or injury from anti-vehicle mines (196) is almost as high as the number from anti-personnel mines (247). A ban on the use of anti-vehicles mines would complete the promise of the Mine Ban Treaty.

Next month, the parties to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons will convene for their annual meeting. One of the major points on the agenda for the CCW is the continued discussion about lethal autonomous weapons (or “killer robots”), but another issue will be the humanitarian impact of anti-vehicle mines. The governments of the United States and Ireland previously supported attempts to address the dangers poses by anti-vehicle mines and reduce their negative humanitarian impact. The government of Russia has been one of the strongest opponents to any new protocol to the CCW that would limit anti-vehicle mines saying that such weapons have military utility and any protocol would not prevent the “irresponsible use” of anti-vehicle mines by “terrorists” and non-state actors, which are the cause of any civilian injuries. The Russian government also feels continued discussion about anti-vehicle mines to be “hopeless” because the “humanitarian concerns regarding these mines have not been substantiated.” The difference in opinions is simple: the Irish have stated that anti-vehicle mines “have clear indiscriminate effects and that these are not adequately addressed in existing IHL [international humanitarian law]” and the regulations imposed by Amended Protocol II of the CCW are insufficient. The Russians state that “full compliance with the IHL norms” and Amended Protocol II are sufficient to prevent any “’specific’ humanitarian threat” from anti-vehicle mines.

The GICHD-SIPRI report clearly demonstrates that the humanitarian impact of anti-vehicle mines to civilian populations is significant and persists for decades after the conclusion of conflict. This report can serve as a basis for new discussions about anti-vehicle mines and the need for their regulation. It is my sincere hope that the US, Ireland and their partners will push for a new protocol that would ban these weapons as the Mine Ban Treaty banned anti-personnel mines. I would hope that any regulation of anti-vehicle mines would at the very least require the following:

- Change production standards of anti-vehicle mines to ensure they are detectable by the same means as anti-personnel mines;

- Require the destruction of any anti-vehicle mines, in the ground or in stockpiles that do not meet this detectability standard;

- Restrict the trade, transfer and export of anti-vehicle mines to the same standards as described under the Arms Trade Treaty;

- Recognize the humanitarian impact outweighs any military utility;

- Requires states and deminers to differentiate between anti-personnel and anti-vehicle mines in clearance reporting.

Michael P. Moore

November 3, 2014