The Impact of Sequestration on US Funding for Mine Action

Posted: February 28, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: landmines, Sequestration, United States 1 CommentThe short answer is nobody knows what the impact of sequestration – the mandated US government spending cuts that go into effect tomorrow, March 1, 2013 – will be on any government programs (Washington Post). The White House has published an estimate of the impacts, but their math follows the “peanut butter” model, in which the 8.2% spending reduction is applied evenly across all programs. A large portion of US support for mine action comes under the Conventional Weapons Destruction (CWD) program, managed by the State Department’s Office of Weapons Removal and Abatement. The funding for the Convention Weapons Destruction program falls under the broader program, “Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining, and Related Programs.” According to the White House, the Nonproliferation etc. account is currently funded at $711 million and under the Sequester, that budget will be reduced by $58 million to $653 million (White House, pdf). That’s if, and only if, the spending cuts are distributed evenly which they won’t be. Even within the Nonproliferation etc. account, cuts are unlikely to be distributed evenly: no politician or bureaucrat in his right mind in this town would allow any reduction in “Antiterrorism” funding and the Obama Administration has made nuclear nonproliferation a priority (more so with the appointment and confirmation of Chuck Hagel as Secretary of Defense). So, cuts to the Nonproliferation etc. account can be assumed to strike the “Demining” and “Related Programs” parts of the account harder than the Nonproliferation and Antiterrorism parts.

Basically, sequestration is likely to reduce the amount of money for demining in the current and future budget years. A good indicator of the extent of the reduction can be found in the comparison of the FY12 budget approved by Congress and the FY13 budget proposed (but never acted upon, hence the Sequester) by the Obama Administration. In FY12, Congress approved $149.1 million for the CWD program. For FY13, the White House requested $126 million, a 16% reduction in funding (Friends Committee on National Legislation). If the Obama Administration was willing to propose a 16% cut in the CWD program without the pressure of mandatory cuts from the Sequester, we can expect to see that at a minimum, the CWD would be reduced to the $126 million level and possibly more to minimize cuts in the politically sensitive Nonproliferation and Antiterrorism accounts. Not good.

However, it should be said that at least under the Sequester, more funding for mine action would be available than has been under the series of continuing resolutions. According to the State Department, “The continuing resolution allows agencies to continue spending at the same rate as during FY12… Accordingly, we have about $20.5 million available [for the Conventional Weapons Destruction program] during the continuing resolution period” which started on October 1, 2012 and concludes March 27, 2013 (Personal correspondence). So for a period of almost six months, the CWD program has been running on a much reduced budget and unable to make long-term plans in the absence of an approved budget.

On the plus side, the same day that the Sequester will take effect, the European Union (collectively the largest donor to humanitarian mine action) will announce “a new Decision in support of the implementation of the Cartagena Action Plan,” the plan developed and approved by States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty to clear mines and provide victim assistance (European Union). March 1, 2013 will be the 14th anniversary of the entry into force of the Mine Ban Treaty so the EU’s Decision will be hailed as upholding the spirit of the Treaty and allowing countries to continue to work towards a mine-free world, while the Sequester in the US will be a blow. On one side of the Atlantic, the glass will be half full; on the other half empty.

Michael P. Moore

February 28, 2013

Where to find the (Unfiltered) Survivor Voice

Posted: February 25, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Advocacy Project, Handicap International, Internet, landmines, Mines Advisory Group, survivors, Twitter Leave a commentIn the modern world of internet, telecommunications, mass media and whatnot, the ability for individuals to find platforms to express themselves is simply astonishing. However, one group I keep looking for and have some difficulty finding is landmine survivors. There are many, many landmine survivor stories available on line, but many of them are filtered through one of the many (worthy) organizations working in mine action. The survivors’ voices are selected for their ability to convey the message the mine action organization needs to communicate, often related to fund-raising. The opportunities to hear directly from survivors in an unfiltered manner are few, but notable. What follows is a non-exhaustive list of survivor voices which provides some sense of the breadth of landmine survivors who are telling their own stories, on behalf of themselves and their peers.

Associations and Organizations

Uganda Landmine Survivors Association (www.uganda-survivors.org): Founded in 2005 and led by survivor and International Campaign to Ban Landmines ambassador, Margaret Arach Orech, the Uganda Landmine Survivors Association (ULSA) is a national organization focusing on advocacy and victim assistance. The Association’s members are locally-based survivor associations that strive to serve the needs of landmine victims in their areas through a range of victim assistance programs, including psycho-social support and economic empowerment.

Afghan Landmine Survivors Organization (www.afghanlandminesurvivors.org and www.facebook.com/afghanlandminesurvivorsorganization): Founded in 2007 the Afghan Landmine Survivors Organization (ALSO) provides peer outreach, vocational training, and advocacy for landmine victims. On behalf of all persons with disabilities, ALSO works on issues of inclusion and accessibility and uses social and traditional media (check out their Flickr page in addition to their Facebook page) to get their message out.

Landmine Survivors Initiative (www.ipm-lsi.org): Founded by the former employees of Landmine Survivors Network’s Bosnia-Herzegovina office, Bosnia’s Landmine Survivors Initiative (“Inicijative preživjelih od mina” in Bosnian) continues to provide peer support and advocacy leadership for landmine survivors in Southeastern Europe.

Saharawi Association of Landmine Victims (www.facebook.com/ASAVIM): The Saharawi Association of Landmine Victims (Asociación Saharaui de Víctimas de Minas, ASAVIM) provides victim assistance and mine risk education services to Saharawi living in refugee camps in Algeria. The Director of ASAVIM participated in the 2012 “Lend Your Leg” campaign.

Individuals

Firoz Alizada (Twitter: firozalizada): Firoz is the Campaign Manager for the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (www.icbl.org) and a landmine survivor from Afghanistan. Firoz lost both legs in 1996 when he was 13 and on his way to school.

Giles Duley (Twitter: @gilesduley, www.gilesduley.com): Giles is a photographer focusing on humanitarian projects after working in fashion and music. In 2011, he lost both legs and an arm whilst on patrol with the US Army’s 75th Cavalry Regiment in Afghanistan. He describes his experience in a TED Talk and in the Channel 4 feature, “Walking Wounded: Return to the Frontline.”

Stuart Hughes (Twitter: @stuartdhughes): Stuart is a news producer for the BBC. He lost a leg in an explosion in Iraq during 2003’s Operation Iraqi Freedom. In 2012, he carried the Olympic Torch as part of the relay prior to the London Olympics.

Channels

The Advocacy Project (www.AdvocacyNet.org): The Advocacy Project (AP) works with human rights and advocacy organizations to build their capacity to advocate for themselves. AP volunteers establish blogs and social media channels for partner organizations and then trains them on their use. In Vietnam, AP supports the Association for the Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities and in Uganda, AP supports the Gulu Disabled Persons Union which has links to the Uganda Landmine Survivors Association.

Landmine Victims Speak Up (www.Landmine-Victims.org): Created by a high school senior in North Carolina, Landmine Victims Speak Up provides a forum for Bosnian landmine victims to tell their stories. I love that this site exists.

Video

YouTube (www.YouTube.com): YouTube is a video sharing site that has been extensively used by mine action organizations for awareness-raising and publicity efforts. While the videos are produced by the organizations, the videos provide survivors with the (edited) opportunity to describe their lives, hopes and needs. Some channels worth checking out are:

- Landmines in Africa ();

- A Mine Free World Foundation ();

- The Advocacy Project ();

- Handicap International (also see channels for HI’s UK, France and Belgium);

- Mines Advisory Group (also see channel for MAG America); and

- United Nations Mine Action Service;

Another video-sharing site is VIMEO but many of the videos available on VIMEO are also available on YouTube (although there may be some deterioration in quality in the conversion from the higher-resolution, better produced material on VIMEO, to the lower-resolution, more accessible YouTube).

If you know of other Survivor Voices in the Internet, please let me know and I will update this list.

Michael P. Moore

February 25, 2013

Looking a Gift-Horse in the Mouth: UEFA gives to landmine victims

Posted: February 20, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Afghanistan, Champions League, Cristiano Ronaldo, ICRC, landmines, Manchester United, Real Madrid, UEFA, Victim Assistance Leave a commentBefore the kick-off of the UEFA (the Union of European Football Associations) Champions League match between Manchester United and Real Madrid at Old Trafford Stadium on February 13, Real Madrid and Portugal star Cristiano Ronaldo presented a 100,000 Euro check from UEFA to the International Committee for the Red Cross to support the rehabilitation of landmine victims in Afghanistan (UEFA). On the surface, this is a great story: raises profile of the landmine issue, funds go to persons who are in great need, etc., but just beneath the surface is the reality. This was a naked ploy to buy goodwill for a stupefyingly rich segment of society.

First, the raw numbers: Ronaldo’s annual salary is 12 million Euros. 100,000 Euros is three days’ wages for him and he did not even contribute to the check, he just carried it and smiled for the cameras. For the 2012-2013 Champion League season, UEFA’s estimated gross commercial revenue from all sources is 1.34 billion Euros (more than the GDP of Liberia). According to UEFA:

Some 75% of the total revenue from media rights and commercial contracts concluded by UEFA, up to a maximum of €530m, will go to the clubs, while the remaining 25% will be reserved for European football and remain with UEFA to cover organisational and administrative costs and solidarity payments to associations, clubs and leagues.

A total of 82% of any revenue received from the same stream in excess of €530m will be allocated to the clubs, with the other 18% allotted to European football and remaining with UEFA for the purposes listed above.

Or, 1.06 billion Euros will be distributed to the participating teams and UEFA will retain 278 million Euros for “organizational and administrative costs and solidarity payments.” The 100,000 Euro check Ronaldo held came from that 278 million Euro pool and represented 0.036% of UEFA’s share of the Champions League revenues and 0.007% of the total revenues produced by the Champions League. In addition, any team that participates in the one of the Champions League’s qualifying stages was guaranteed a payout of 140,000 Euros, win or lose so even the worst team in the competition (San Marino’s Tre Penne) received more money from UEFA than landmine victims did. And there are a damn sight more landmine victims in Afghanistan than there are players on all the Champions League teams put together. In fact, there might be enough landmine victims in Afghanistan to fill Wembley Stadium where this year’s Champions League final will be held.

I don’t for a moment begrudge the Red Cross taking this money: they will put it to good use and the opportunity for some free advertising and awareness-raising is welcome. I question UEFA’s intentions. For UEFA, 100,000 Euros is meaningless, but it makes them (and Ronaldo who holds the check) look like good corporate citizens. If UEFA were serious about giving money to landmine victims there are other options.

First, within the UEFA membership are several mine-affected countries with large landmine victim populations that would benefit from UEFA funds: Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Cyprus, Macedonia, Georgia, Greece, Israel, Montenegro, Serbia, Slovenia, Turkey and Ukraine. Second, instead of having Ronaldo give a check to the Red Cross’s director of human resources, he could give the check to an actual landmine survivor, in Afghanistan. Third, UEFA could give more. 0.007% is such a small amount as to be negligible; it’s a rounding error, not a contribution. Last, UEFA could give the check on a more important date.

In 2012, 300 million people tuned in to watch the Champions League final. That’s more than watch the Super Bowl and the value of the free advertising such a showcase would offer to landmine survivors and the Red Cross is far higher than that of the first leg of a quarter-final match. Yes, the Real Madrid-Manchester United game probably got a lot of eyeballs, but not as many as the Final would, and the alternative quarterfinal matches included the far lower profile games, Malaga-Porto and Shakhtar Donetsk-Borussia Dortmund. Had the check ceremony been held at one of those games, the attention would have been far less. A quarterfinal is not the Final and by placing the ceremony at the Final, UEFA would be demonstrating a greater commitment to the cause in terms of profile and lost revenue.

So, come on, UEFA. Show us how much you really care.

Michael P. Moore

February 20, 2013

A Success Story in Numbers: the Improving Aftermath of Conflict

Posted: February 19, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Africa, Landmine Monitor, landmines 1 CommentWhen I started this blog, I had in mind the fear that new conflicts would lead to new use of landmines. This has been proven true in Libya (The Monitor), Sudan (IRIN News) and Mali (Agence France Presse) in just the last two years. However, the question remains as to whether this new use is part of a trend or just an anomaly? The groups using landmines in Libya, Sudan and Mali were not likely to be dissuaded from their use by international pressure or humanitarian concerns, so further investigation was warranted. Using the available data, I’ve tried to statistically review the situation.

When we talk about landmines, one of the biggest points raised is the fact that landmines and other explosive remnants of war (ERW) go on killing many years after a conflict has ended. In Egypt, landmines left over from World War II threaten the lives of Bedouins living in the battlefields of El Alamein (Al Jazeera); in Laos, ordnance dropped by American airplanes almost half a century ago prevent land from being used for agriculture (The New York Times); in Belgium a woman, not even thirty years old, is the youngest survivor of the First World War, having accidently put a bomb on top of a fire during a school camping trip (The Independent). These are very real examples, but the statistics show a definite and laudable trend: fewer and fewer people are injured every year as a result of past conflicts.

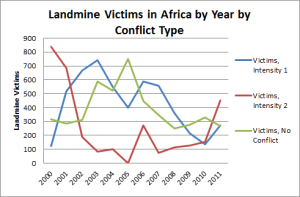

From 2005 to 2011, the number of persons killed or injured by ERW from conflicts that ended more than two years previously has dropped from almost 2,800 people to less than six hundred (see category “No Conflict” in the chart below). At the same time, the number of people killed or injured in the immediate aftermath of a conflict (“Conflict Ended”) has remained at or below one hundred persons per year (the one exception is Colombia in 2007, when the conflict in the country briefly subsided before resuming in 2009; I treat this circumstance as a statistical outlier). There are three factors playing into this: 1) because of the global stigma against their use, fewer landmines are being used, 2) humanitarian groups are getting better at reaching refugee and displaced populations with mine risk education programs, and 3) demining activities continue around the globe. I don’t dare to say which of these is the biggest contributor to the decline in landmine casualties: depending on the context and country each could be the leading factor. Another, possibly hidden, cause may be that known or suspected minefields are simply abandoned and not subject to re-use after conflicts.

On the downside, the number of landmine and ERW victims in countries in conflict has remained constant over the last several years at around 3,000 individuals per year. This number is due to the use of new landmines in countries like Pakistan, Myanmar and Colombia but also due to refugees and displaced persons fleeing conflict and traversing old mine fields in countries like Afghanistan. In these countries, the political solution of conflict termination must precede attempts to clear landmines and reduce casualty rates. However, humanitarian agencies do work in the conflict space to provide mine risk education and create safe spaces for displaced persons to gather which probably reduces the number of victims somewhat.

If we look deeper into the numbers, focusing solely on Africa, we see some of the same trends continuing and new ones emerging. In his book, Fate of Africa, Martin Meredith called the first years of the 21st Century, some of the most violent in Africa’s post-independence history. The data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program supports his assertion with 14 separate conflicts across the continent in 2000 and 2001 and 12 in 2002. However, the total number of conflict declined to a low of just five in 2005, before climbing back up to 12 in 2011.

Beginning in 2005, the number of landmine victims in conflict-free countries fell, similar to how the number of victims in all conflict-free countries fell as we saw above. In addition, the number of landmine victims per conflict declined in the same period, from almost 120 victims per conflict to about 35 victims per conflict. Except in 2011. In 2011 with the Arab Spring revolts against Libya, the renewed conflict between Sudan and South Sudan and the invasion of Somalia by Kenya to wipe out Al Shabaab, three violent (Uppsala calls them Level 2 Intensity) conflicts broke out. In these conflicts, an average of more than 150 persons were killed or injured by landmines as the total number of Africans killed or injured by landmines increased by 50% over the numbers seen in 2009 and 2010.

As I stated above, these conflicts may be unusual, but unfortunately they reverse the gains made to date. In 2000, there were six Level 2 intensity conflicts and 840 people were killed or injured by landmines in those conflicts. In 2005, there were no Level 2 intensity conflicts and a clear trend had begun where fewer and fewer landmines claimed victims in Level 1 Intensity conflicts. As the Level 2 conflicts broke out, we see a slight uptick in the number of victims per Level 1 conflict. Fortunately the number of victims in conflict-free countries continues its downward trend, a trend that, like those above, suggests when conflicts end, the number of landmine victims will gradually decrease.

Michael P. Moore

February 19, 2013

Data for this post came from the Landmine Monitor (www.the-monitor.org) and from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/UCDP/).

The Month in Mines: January 2013 by Landmines in Africa

Posted: February 9, 2013 Filed under: Month in Mines | Tags: Africa, Algeria, Angola, landmines, Mali, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Uganda, Zimbabwe 1 CommentI could not come up with a good, broad narrative for January in regards to landmines on the continent. There is some very bad news from Mali and Algeria with reports of new landmine use by rebel groups and there is some very good news as Somalia, Angola and Uganda continue to make progress towards assisting survivors and clearing minefields. However there is also a cautionary tale about the danger of tampering with landmines from Zimbabwe (in a story that if it were not true, no one would believe it) and from Angola a reminder of the legacy of Princess Diana which also, unwittingly, reveals the desperate state of landmine survivors there. In between we also hear from Rwanda and the Sudans.

Algeria

Whisper it, but the truth is coming out: Gaddhafi’s arsenal is in the hands of people that no government would want it to be in. With so much focus by the United States on securing the anti-aircraft rockets known as MANPADS, the tens (if not hundreds) of thousands of small arms and explosives that Gaddhafi had stockpiled were allowed to be carried out of Libya in 2011. An Islamist group seized control of a natural gas facility run by British Petroleum and Norway’s Statoil in Ain Amenas, Algeria holding dozens of hostages. Using Belgian-made landmines spirited out of Libya, the militants set up defensive perimeters to try and slow down the Algerian forces that eventually overpowered and killed the militants (along with several hostages, others of whom were killed by the militants). There is concern that if landmines and other weapons are in the hands of Islamist militants in Algeria, they could also be in the hands of others, including the rebels in Mali (The Guardian; The Associated Press).

Mali

When the French military began its operations against the Islamist militants who had seized northern Mali, there were initial reports from the Islamists themselves that they would use landmines to protect the territory they controlled. World Vision raised the alarm about the potential danger of landmines less than a week after the French forces arrived, using mine-risk education to warn children of the dangers of tampering with landmines and other unexploded ordnance (All Africa). As the French forces moved northward and being mindful of the warnings issued by the Islamists, they moved slowly to ensure that roads to and from Diabaly were free of landmines (Voice of America; All Africa).

On January 31st, the threats of landmines became reality as two Malian soldiers were killed when their vehicle drove over a landmine on the road between Douentza and Hombori. The two towns had been liberated from Islamist control by French forces and according to a security source, “We strongly suspect the Islamists placed this landmine. It happened in an area which had been under their control. But we don’t know if it was placed before they left or if they came back to place it” (The Daily Monitor), but later reports suggest that the mine was laid after the area had been recaptured (France 24). In another, apparently separate incident also on January 31st, four more Malian soldiers were killed and another five people injured by a landmine on the road between Gossi and Gao (The Guardian; Voice of America). Gao had been the site of the first reports of landmines several months ago and this incident could be the first confirmation that the Islamists’ threats to use landmines were true.

Sudan and South Sudan

In Sudan’s Blue Nile State (on the border of South Sudan and Ethiopia), landmines are prevalent in many areas. The United Nations (presumably the UN’s Mine Action Service, UNMAS) and the national mine action authority will train demining teams to clear 15 hazardous areas around the locality of Bao. Blue Nile state continues to be plagued by conflict as a result of unresolved issues from the civil war that led to the secession of South Sudan, but the promise to clear mines in spite of the conflict is promising to those who live in and around Bao (Sudan Radio).

The disputed Abyei region remains a flash point between the two Sudans and South Sudan has recently accused Sudan of trying to unilaterally resolve the Abyei issue, which in all fairness is what Khartoum has tried several times. The presence of landmines in Abyei ensures that the thousands of residents who fled the region during fighting in 2011 remain in displacement camps, unable to return home. With a new referendum on Abyei’s future planned for October, the continuing absence of those displaced individuals could affect the referendum’s outcome, demonstrating the political (in addition to humanitarian) impacts of landmines (All Africa).

In Juba, UNMAS, the South Sudan National Mine Action Authority and mine action partners hosted a “Mine Action Open Day” to highlight the impact of mine action in South Sudan. Residents could observe mine action techniques including “demonstrations of dogs detecting explosive vapours, manual mine clearance road surveys, battle area clearance, explosive ordnance disposal and equipment used in demining activities.” The partners reported that 2 million people had received mine risk education, and 50,000 landmines and unexploded ordnance had been cleared from 71 million square meters of land. To reinforce the importance of mine action, survivors of landmines also took part and the father of a six year-old survivor “told the attendees to heed the danger landmines and other unexploded ordnances posed, as they discriminated against neither age nor class” (ReliefWeb).

Uganda

Despite the massive corruption scandals in Uganda that have caused some donors to suspend all aid to Uganda, reconstruction progress is being made in Northern Uganda, the region affected by two decades of rebellion from the Lord’s Resistance Army. Demining, such as that done by the Danish Demining Group, has allowed access to agricultural lands which had previously been dangerous. With 80% of the population of Northern Uganda dependent upon small-scale farming, any land lost to landmines equals livelihoods lost (All Africa). Still more needs to be done to ensure that victim assistance services are available to landmine survivors (and the corruption scandals have already stolen money meant to such programs). The knee-jerk reaction of donors to suspend aid or demand its return is wrong. The money is gone; by the time the reports are in the papers, the cash has been pocketed and laundered and any funds returned are not coming from those who stole it, but from those who were the intended beneficiaries of the aid. If the Office of the Prime Minister in Uganda is corrupt – which it is – then work around it. Don’t punish those who need the assistance most.

Rwanda

Rwanda presents us with a reminder of one of the most insidious issues facing landmine survivors: discrimination and prejudice against persons with disabilities. A report tells the story of a survivor, Sifa, who lost her legs during the 1994 genocide and how in the year since, she has faced sexual assault, social exclusion and is utterly dependent upon the charity of others. As the mother of a child of rape, Sifa also faces constant reminders of her life experiences and while “the baby was not a source of joy,” she still feels hurt because “there is nothing I can do to help her!” In the story’s one positive note, Sifa has not given up for being independent one day and declares that “When I find enough money I will rent my own house,” and be able to look after her daughter. Unfortunately, with no schooling and no vocational training, Sifa’s employment options are limited (All Africa).

Somalia

In the semi-autonomous region of Somaliland, the HALO Trust continues to work to clear landmines and unexploded ordnance left over from wars in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. Many of the minefields are along the borders with Ethiopia and remain uncleared while some urban areas, including the capitol, Hargeisa, remain heavily mined. As in other mine-affected areas, individuals have “harvested” mines to re-use them exposing individuals to grave danger. Mine clearance in Somaliland is especially tricky because most mines have only minimal quantities of metal making them difficult to detect using metal detectors, especially in the metallic soils. Despite these problems, after a dozen years of work, the HALO Trust estimates that another five years of work remains to clear the remaining 280 hazardous areas, of which about three-quarters are roads. By clearing the roads of mines, residents will be able to access markets which until now have been too dangerous to use (The Somaliland Sun).

Elsewhere in Somalia, specifically in Mogadishu, security forces have been working to arrest “individuals suspected of creating instability in the capital.” After rounding up more than 3,000 individuals, 259 remain in custody. In the security sweep, the authorities confiscated “landmines, bombs and ammunition for heavy weapons such as bazookas, AK-47s and other automatic machineguns” (All Africa). Such security operations are important in a country where the “amount of arms owned by civilians exceeds the amount owned by the weak state by between five to seven times” and an individual can purchase a landmine for $100 or a Kalashnikov for $140 from one of the 400 “potent” weapons vendors in Mogadishu’s Bakara Market (As Safir).

Zimbabwe

What follows is a cautionary tale that includes witchcraft, greed, conmen and landmines. If it were not true, I would never be able to believe it. I have compiled this from several sources (All Africa; All Africa; The Sunday Mail; The New Zimbabwe; All Africa; All Africa; News Day).

On January 21st, a massive explosion ripped through Chitungwiza, a densely populated suburb just south of Harare. Six people were killed by the blast, five instantly including a seven-month-old baby, the sixth succumbed to his wounds several days later. The explosion took place at the home of Speakmore Mandere, a local healer who was known as Sekuru Shumba. Shumba was reputed to be able to perform traditional magic and healing. At the scene, investigators found a clay pot and because of the injuries to a local businessman – he was “torn apart at the waist area” – investigators believed that the clay pot was the source of the blast and at the time of the explosion, the businessman was straddling the pot. Four possible causes of the blast have been identified:

- A local businessman, Clever Kamudzeya, had secured the services of a money-making goblin (through another healer). The goblin helped Kamudzeya grow his business, but the goblin had started to make demands of Kamudzeya and so Kamudzeya went to Shumba to dispose of the goblin. The blast occurred after three days of ceremonies when Kamudzeya brought the goblin to Shumba to be destroyed. The goblin fought back and destroyed itself and 12 houses.

- Shumba manufactured a lightning bolt but the bolt struck its source instead of its intended (and unknown) target.

- Shumba was conducting an enrichment medicine (muti) using a rare rodent-like animal, the sandawana. According to a member of the Zimbabwe Traditional Healers Association, enrichment spells using the sandwana are “very dangerous” and “not recommended to be done in a house” and “usually discharged in the bush” because “it can backfire.”

- Shumba and Kamudzeya were tampering with an anti-tank landmine in an attempt to extract “red mercury” from the mine.

Red mercury does not exist. In a scam that began in the 1970s, conmen would sell red powders to people looking for get-rich-quick schemes and tell them that the powder was rare and used in bomb-making and therefore valuable. In Saudi Arabia, people were convinced that red mercury could be found in and extracted from old Singer sewing machines which raised their price five hundred-fold. More recently, items of unexploded ordnance, including anti-tank mines, have been sold for $300 in Zambia, Angola and Zimbabwe by conmen who tell the buyers that if they can extract the red mercury, the seller could then get thousands of dollars for the non-existent material. The explosion in Chitungwiza is the third known occasion of Zimbabweans trying to extract red mercury from explosives. In the previous events, four people in Waterfalls were injured trying to open a grenade and in Manicaland, two conmen were arrested trying to sell unexploded mortars.

What likely happened was that Clever Kamudzeya bought an anti-tank mine and then approached Sekuru Shumba with the hope that Shumba could enrich or increase the amount of red mercury in the mine through magic. Shumba reported charged Kamudzeya $15,000 for the procedure so Kamudzeya must have believed that the red mercury existed and was very valuable. Both men paid for their belief with the lives and the lives of four others.

Please, please, please do not tamper with landmines or unexploded ordnance.

Angola

This space often promotes Angola as a country that is making slow but continuous progress towards becoming mine-free and for the most part, the news about Angola this month was positive and covered much of the country as various entities provided reports of their 2012 accomplishments. In Bie Province, the HALO Trust cleared 125 landmines and another 582 pieces of unexploded ordnance (All Africa). In Cunene Province, the Angolan Armed Forces cleared 10,000 explosive remnants of war (ERW) from 800,000 square meters (All Africa) while the National Demining Institute (INAD) cleared another 4.5 million square meters of nearly 30,000 ERW, including 80 landmines (All Africa). In Huambo Province, INAD cleared almost five thousand pieces of ordnance from 1.3 square kilometers (All Africa). INAD also cleared 11 million square meters of land in Lunda Norte Province of 33,000 ERW and 85 landmines (All Africa).

However, some obstacles still remain. In Cunene Province, as the HALO Trust was working, they also discovered nine previously unknown minefields (All Africa). In Moxico Province, the local police found 51 landmines that had been collected and stored by a local man on the playground of his home, this despite the efforts to reach millions of Angolans with warnings about the dangers of tampering with landmines (All Africa). In Lunda Norte Province, INAD recognized that its deminers were underpaid and officials would were committed “to improving the work conditions of staff this year.” I’m not sure exactly which work condition need to be improved, but I would think deminers would need to be working in the best conditions possible, if only for their own security (All Africa).

Lastly, in the same month that Angola named President Eduardo Dos Santos’s daughter, Isabel, as Africa’s first woman billionaire – mostly as the result of her access to the nation’s oil wealth and large shareholdings in national media and telecommunications companies (The Guardian) – we also heard about the young landmine survivor, Sandra Tigica, who was photographed with Princess Diana in 1997. A new film about Princess Diana starring Naomi Watts is in the works, and to re-create the scene between Diana and Sandra, Sandra’s eight-year old daughter was filmed with Naomi Watts. The Daily Mail (I know, not the greatest source of journalism, but bear with me) took advantage of the opportunity to interview Sandra and inform its readers about how meeting Diana changed her life.

The Daily Mail quotes Sandra, “Princess Dianan helped our country. It is a much safer place thanks to her… [Diana] brought hope to Angola.” Sandra mentions that she watched the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton and says that Kate should come to Angola to continue Diana’s work. The photo of Sandra and Diana is hung on the wall of Sandra’s home and because the photo has been re-printed in schoolbooks, Sandra is often recognized because of it. But that’s the positive side of the story. In the interview we also get a sense of the difficulties of life in Angola, even for the most famous landmine survivor in the country.

While Sandra has a prosthetic leg, she prefers to use crutches because the “legs made here [in Angola] are too heavy and I can’t move properly.” Despite having a job and a husband in the army, Sandra’s family of six lives in a “hut with a corrugated iron roof” that measures 800 square feet. Sandra has the perception that “people have started to forget” about the threat of landmines in Angola. Lastly, while expressing her excitement at the thought of featuring in “a big film,” Sandra says “I don’t a have a TV so cannot watch it.” Does everyone deserve or need a television? No, but the fact that Sandra’s story has now been used twice, once to promote the landmine cause with Princess Diana and once to promote a Hollywood movie, I would think she should at least be able to see herself as portrayed by her own daughter.

Michael P. Moore

February 9, 2013

Movie Review, “Surviving the Peace: Angola”

Posted: February 7, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Africa, Angola, landmines, Mines Advisory Group 1 CommentLast night I attended the United States premiere of the documentary, “Surviving the Peace: Angola,” produced by MAG America. The film, created by the firm Media Storm, demonstrates the impact of landmines on Angola and MAG’s efforts to rid the country of this scourge. Through three characters: Eron, a former soldier and now a deminer; Minga, an eight year-old girl who had been injured by a mine three years before the film was made; and Minga’s grandmother who raises her, the film shows hope (in the form of Eron), but also the terrible toll landmines can take on individuals (Minga), their families (her grandmother) and communities. The filmmakers inter-cut scenes of Minga and her grandmother with scenes of Eron working in the minefields.

In the scenes with Minga and her grandmother, we watch as Minga learns to read and write despite having been blinded by a mine. We hear how Minga’s grandmother fears for Minga’s future (she tells Minga that one day Minga will be on her own and have to care for herself), but also how Minga’s grandmother has lost her livelihood having to look after Minga full-time. Minga tells us how she was injured: in an all-too-frequently-told-story, Minga came upon a “tuna can” in a field and poked it with a stick. For dramatic effect, the filmmakers have been showing scenes of explosive disposal as Minga talks, culminating with the detonation of several shells and landmines, just as she tells us she poked the can with a stick. We see the blast of the unexploded ordnance as we are forced to think of a five-year old girl setting off a landmine in a field.

The film is part of a new campaign by MAG America to raise US $100,000 to support mine-risk education in Angola to help prevent future injuries like those Minga experienced. In a brief segment of the film, we see MAG staff teaching a classroom of children from Minga’s village about the dangers of landmines and specifically using Minga’s experience as a cautionary tale.

Michael P. Moore

February 7, 2013