Every Tool in the Toolkit, The Royals

Posted: January 4, 2017 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Angola, HALO Trust, landmines, Princess Diana Leave a commentThis month marks the 20th anniversary of Princess Diana’s visit to Angola. During that visit she donned protective gear and walked through a recently cleared minefield and met with landmine victims at the Red Cross’s prosthetic clinic. At this time, negotiations on the Mine Ban Treaty were ongoing and Diana’s visit to the minefield and her subsequent advocacy helped galvanize public opinion against anti-personnel landmines.

In February 1997, BBC1 aired a special on Diana’s trip which is available in three parts on YouTube:

Diana’s visit was coordinated by the British Red Cross and the minefield aspects were last minute additions to the program. I have been told that the HALO Trust team received a call from the trip organizers one afternoon asking if Diana could visit a minefield the next day. Recognizing the opportunity, the Trust made the necessary arrangements. Looking at the photos and the video, I am struck by how terrifying the experience must have been for Diana. The civil war in Angola had only ended a couple of years before (and would re-ignite soon enough) and despite wearing protective gear, you will notice that no one is walking with her in the recently cleared minefield and humanitarian demining was still in its infancy. Every step she took she could see the warning signs and the white stakes you see mark where a landmine had been laid and removed.

And yet, she managed a smile for the cameras.

Since Diana’s death in August 1997, other members of royalty have stepped forward. Jordan’s Prince Mired bin Raad serves as the special envoy for universalization of the Mine Ban Treaty and has traveled to multiple countries including China, the United States, Tonga and Peru to encourage accession to the Treaty. Princess Astrid of Belgium serves in a similar role, promoting the Mine Ban Treaty and advocating for the rights of landmine survivors. Prince Harry, Diana’s younger son, has also carried on her mantle serving as the patron of the HALO Trust’s 25th anniversary appeal and traveling to Mozambique and Angola to personally witness the mine clearance work. The presence and interest of royalty in landmines helps keep the focus on the subject and ensures that public attention and support continues.

The 20th anniversary of Diana’s visit affords an opportunity to review what has been done over the last two decades. The results are astonishing. The below picture shows the comparison of what the minefield looked like during Diana’s visit and what it is now: a city street with no signs of its past as a minefield.

In addition to the progress on landmine clearance in Angola, the victim assistance situation in Angola and Bosnia which was a large focus of Diana’s advocacy can also be reviewed.

When the movie, Diana, came out a couple of years ago, the Daily Mail tracked down the survivor in the below photo and gave an update on her life since meeting Diana. The 20th anniversary is another opportunity to check in on Sandra and the other survivors Diana met.

In August of 1997, Diana made her last formal trip, visiting landmine survivors in Bosnia with the founders of Landmine Survivors Network. In the years following that trip, an annual sitting volleyball tournament was held in Diana’s honor, emphasizing her role in bringing attention to the issues in Bosnia. If the anniversary of Diana’s visit leads to a 20-year review of the progress in Bosnia, that would be a positive.

Michael P. Moore

January 4, 2017

moe (at) landminesinafrica (dot) org

Blogging Angola: Cuito Cuanavale – South African Tanks, Angolan Mines

Posted: June 23, 2016 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Angola, HALO Trust, landmines 1 CommentCuito Cuanavale is Angola’s Gettyburg, its Dien Bien Phu, the great nation-making battle. The biggest tank battle on the African continent since World War II’s El Alamein, Cuito Cuanavale is the battle that broke Apartheid South Africa. On one side was the Angolan army (FAPLA) supported by thousands of Cuban troops; on the other, the rebel group UNITA and hundreds of South African conscripts. And since this was the Cold War, Angola was supported by Soviet money and materiel; South Africa and UNITA operated under US sponsorship.

In Angola’s far southeastern province of Kuando Kubango, Cuito Cuanavale was an otherwise nondescript spot on the map but after an attempt by FAPLA to destroy UNITA in the town of Mavinga, a South African counter-attack drove FAPLA 200 kilometers back to the high ground above Cuito Cuanavale with the Cuito River protecting FAPLA’s flank and rear. The airstrip in Cuito Cuanavale allowed for rapid re-supply and convoys of hardware pounded down the road from Menogue. FAPLA and the Cuban army, at the orders of Fidel Castro himself, decided to hold the line at Cuito Cuanavale and the mine-laying began in earnest. There is perhaps a greater concentration of anti-tank mines here in Cuito Cuanavale than anywhere else in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The HALO Trust has been clearing landmines from Kuando Kubango province since 2002 and from Cuito Cuanavale since 2005. Throughout Angola, HALO has cleared about 90,000 landmines, of those 50,000 came just from Kuando Kubango and of those 30,000 came from Cuito Cuanavale. Cuito Cuanavale deserves its title as the most mined town in Africa and it was the next spot on our itinerary.

Itinerary: Malanje to Menongue; Menongue to Cuito Cuanavale

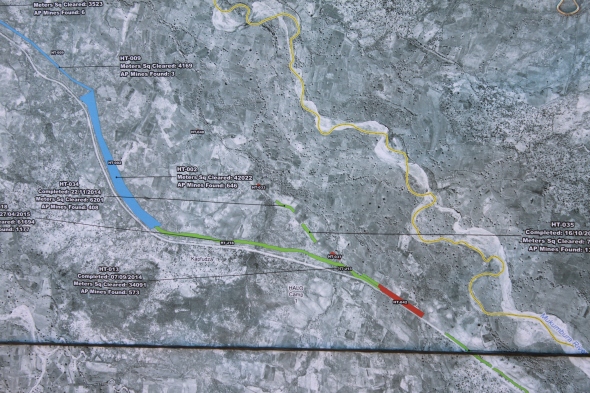

To get to Cuito Cuanavale and the HALO Trust working area, we flew from Malanje to Menongue, the capital of Kuando Kubango. In Menongue we met with the vice governor and the local CNIDAH office. The governor thanked the donors for their support and admitted, “There’s still a lot to be done,” to clear the remaining mines. The provincial coordinator for CNIDAH showed us the operational map for the province.

CNIDAH’s operational map of Kuando Kubango province; Cuito Cuanavale is marked by the red rectangle

They use the map to monitor the activities of the operators, including government agencies, national NGOs and international NGOs. The office documents demining, risk education, victim assistance and landmine accidents. In 2015, just under 3 million square meters of land was cleared, removing over 4,000 mines and 2,000 pieces of UXO. 7,000 people received mine risk education and another 7,000 received some victim assistance services (with a population of just over 600,000, that means 1% of the province received victim assistance, a staggering total that I will be following up on). There were also five landmine accidents which injured four people and destroyed one vehicle. In 2013, there were 13 accidents which left one dead and eight injured.

From Menongue, we took a short hop flight to Cuito Cuanavale where the airstrip had been rebuilt to accommodate the annual celebration of the battle of Cuito Cuanavale on March 23. Of course, the drainage around the new airstrip wasn’t done properly and during the first big rainstorm the run-off took out HALO’s camp, a couple of houses and the local church. The drainage has been fixed and HALO’s camp has been re-located outside of town, next to the massive water and energy plant. In HALO’s map below the town name is at the end of the same airstrip and the minefields are marked in green (for cleared minefields) and red (for fields yet to be cleared).

The HALO Trust’s map of minefields around Cuito Cuanavale; Task 320 is marked by the yellow oval

The HALO team, led by Tony and Gerhard, showed us around Task 320, a minefield laid by the Angolan army after the battle. Before the tour began, we had to don protective gear and sign the guestbook, which also recorded our blood types.

The task is nearly all anti-tank landmines with some anti-personnel mines as “keepers” to keep the anti-tank mines from being lifted. Similar anti-tank mines had destroyed three South African tanks that are now the highlights of the tour of the battlefield.

A South African tank disabled by Angolan mines and abandoned during the battle of Cuito Cuanavale

Task 320 consists of two rows of mines between which the local villagers have started cultivating cassava. There are paths that traverse the lines of mines from the small collection of houses down to the river. In 1999, a person crossing the minefield triggered a mine and later died at the hospital in town. By clearing the minefields, forty families will benefit, directly and indirectly, from increased agricultural land and safe passage through the area.

Hand drawn map of Task 320; the lines of mines are marked by the dashed red line; the community is circled in green; the site of the 1999 accident is marked by the yellow circle

The minefield itself is nasty, no other word for it. There are hundreds of anti-tank mines in the rows, some with anti-personnel mines nearby, many without. Fortunately only a handful of unexploded shells have been found in the area, leaving most of the clearance fairly uncomplicated. The sandy soil is easy to excavate as well. But there are just so many of them. In the picture below there are nine and many more just beyond.

Anti-tank mines laid by the Angolan army and waiting demolition by the HALO Trust

The anti-tank mines are not destroyed immediately as doing so would spread metal fragments throughout the site. Fortunately, the weight of a human being won’t set off these mines so leaving them in the ground for a few days is not a problem. The anti-tank mines are clearly marked and usually the sand is put back over them to reduce any temptation to tamper.

Marking an anti-tank landmine

At the end of the month, all of the anti-tank mines will be destroyed in a couple of days, leaving rather big holes.

The crater left by the demolition of an anti-tank mine

Anti-personnel mines are destroyed the same day they are found.

Stake marking the location of a Russian-made MAI-75 anti-personnel mine; found and detonated on April 21, 2016

Living on the margins

Angola is home to Africa’s first female billionaire, Isabel dos Santos, but the majority of the people are on less than $2 per day. The people by the minefield would probably feel like they hit the lottery to see $2 in a day. Hardscrabble, eeking out an existence by subsistence farming with minefields limiting their ambitions. But life goes on here.

Because we could all use a photo of a napping puppy; this little one was behind a hut in the community near Task 320

The few families in the community (one could not call it a village) came out and greeted our party (which between the deminers, the local administrators, the Angolan soldiers and us, easily outnumbered the community members).

Members of the community living near Task 320 and HALO employee Gerhard Zank, Programme Manager for Angola

Just across Cuito River from this community is the new airstrip, a new hotel, Chinese-run utility plants and the massive new battle memorial. But the only visible investment in this community is the corrugated roofs, which the community members hold in place using Soviet recoilless rounds scrounged from the battlefield.

Gerhard checking the Soviet munitions on the roof; they were full of sand

This task will be completed by the end of August. At that time, HALO will need to assess its financial situation and decide how to proceed. Kuando Kubango province won’t lack for mines if HALO chooses to continue to work in Cuito Cuanavale or elsewhere in the province.

Sign on the road to Mavinga

Only the first 40 kilometers of the road to Mavinga have been cleared; in that span 50 minimum metal anti-tank mines were found and dozens more would likely be found if one went looking. South African laid minefields, which covered the retreat of the South African army from the battle of Cuito Cuanavale, make up a 30 kilometer-long barrier to the east of the town. Beyond Mavinga, minefields can be found all the way to the Zambian and Botswanan borders. And these minefields are linked to just a brief period, maybe a year or so between 1987 and 1988, of Angola’s forty years of wars. HALO has had mine-clearing activities in four provinces: Kuando Kubango, Bié, Huambo and Benguela; and survey work in Kwanza Sul and Huila with plans to survey Namibe and Cunene provinces. Those provinces have their own particular histories and related landmine contaminations. The urban areas have been the focus of demining and the rural areas, like the community pictured above, will be the last to benefit. In other words, those whose lives would be immediately improved by additional farmland and safe paths, are still waiting and will continue to wait without additional support for groups like the HALO Trust. The battle ended nearly thirty years ago, and every March 23rd, the great and the good of Angola come to Cuito Cuanavale to celebrate it. For the other 364 days of the calendar, the people of the minefields should be remembered and assisted.

Michael P. Moore

June 23, 2016

moe (at) landminesinafrica (dot) org

A Day in the HALO Life

Posted: July 20, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: demining, HALO Trust, landmines, Zimbabwe Leave a commentDuring my recent visit to Zimbabwe I had the incredible opportunity to accompany the HALO Trust to its worksite on the Mozambican border, a four hour drive from Harare. With a team of 150 people, many of them locally-hired deminers, but also a large number of experienced deminers who had cleared mines in Afghanistan, Lebanon, the Falkland Islands and elsewhere. There is also an all-female section of deminers. Each month the team works 22 days straight and then has eight days off; almost all of the team lives in one of two camps (some of the locally-hired crew go home, but for the first several cycles even the locally-hired deminers stayed in camp). The team starts early and works in 30 minute shifts followed by 10 minute breaks to help maintain concentration.

Mine clearance in this part of the country is simplified by the fact that most of the mines were laid in a very regular and predictable pattern as seen below. In 1998 – 2000, Koch MineSafe cleared the Cordon Sanitaire minefields (at the top of the picture) and the two rows of Ploughshares (a directional fragmentation mine placed upon a stake at roughly head height) closest to the Cordan Sanitaire. That left the reinforcement minefield and the row of Ploughshares closest to the reinforcement minefield. In the middle of the reinforcement minefield, marked by the solid line with “x”s on it, was a barbed wire fence. All that remains of the Ploughshares and the barbed wire fence are the stakes in the ground that held the mines and fence posts. These stakes help HALO determine where the mines are because the mines really do follow the pattern in the diagram.

HALO found these four mines (the white stakes show the location of cleared mines) in the exact pattern described by the Rhodesian mine layers; when the team finds one mine, they can generally predict the location of the rest.

Finding the Ploughshares stakes also helps as each Ploughshare was protected by two “keepers,” anti-personnel mines that prevented tampering with the Ploughshares. Through fires and animal accidents, all of the Ploughshares have been detonated but many of the stakes remain.

However, the stakes can also serve as good digging tools and many have been collected from the minefields despite repeated warnings about the risk:

Despite the relatively good conditions for landmine clearance, a lot of work is needed because most remain buried and covered by underbrush. A few mines have been found on the surface, like this one, but they are rare.

The work day starts very early with a morning reveille and parade to go over issues and remind everyone to take care. The day I arrived a deminer had been bitten by a snake so the next day’s reveille was an opportunity to tell the team that he was fine and would be returning to work soon.

As soon as the light is good for working, the team is in the field to be able to end the work day before the heat of the mid and late afternoon. To get from the camp to the work sites, the teams travel in vehicles that had been acquired from a German safari company:

In the field, the deminers mark out their work areas using red stakes and string. Some work horizontally (covering several meters of width and less than a meter depth), others work vertically, one square meter at a time. In this photo, the deminer is sweeping a horizontal work area with a metal detector set to the highest level of sensitivity. Before he could start the sweep with the mine detector, he first had to clear all of the brush, bushes and trees from the area.

When the detector indicates the presence of metal, which could be a mine, shrapnel from a Ploughshare, an old piece of barbed wire or any number of other items, the deminer marks the spot with wooden tab:

For my benefit, the deminer pointed out the red wooden tab:

The wooden tab is then “boxed” in and the deminer preps the ground for digging.

The deminer then digs out the ground in front of the “box” to a depth of 20 centimeters. This is the depth required in HALO’s standard operating procedures and corresponds to the maximum depths at which HALO has found buried mines in this area.

In areas with lots of metal contamination (like where a Ploughshare exploded and the shrapnel has spread out), the deminer may need to fully excavate the work area because the metal detectors cannot identify a single signal.

When a mine is found, the deminer will mark the location using a red area and call over one of the section leaders. Because of the instability of the South African landmines that the Rhodesians used, section leaders are responsible for “lifting” the mines from the ground.

The section leader patiently digs the mine out of the ground. Here’s one showing off his work:

All cleared mines are then collected in a safe location for destruction later in the day.

Once a mine is cleared, HALO places a white stake where the mine was found. Each white stake lists the date the mine was cleared, the type of mine found and the depth of the mine below the surface.

When the deminer declares an area cleared of metal, the section leader will re-scan the area with a metal detector. If the deminer has missed any metal, the deminer receives a warning. Too many warnings and the deminer is dismissed.

At the end of each work day, all of the mines cleared that day are destroyed. The HALO Trust does not have approval from the Zimbabwean government to import or use explosives for demolition so it burns each mine. Each mine is placed in a metal box filled with flammable material, in this case sawdust soaked in flammable liquid.

Section leaders ignite all of the mines at once. Eight were burned on the afternoon I was there.

In the course of the burning, the explosive material burns away but the detonator still explodes in a somewhat unsatisfying flash and puff of smoke:

In the course of the burning, the explosive material burns away but the detonator still explodes in a somewhat unsatisfying flash and puff of smoke:

After the mines are destroyed, the teams pile back into the safari vehicles and head back to camp.

After the mines are destroyed, the teams pile back into the safari vehicles and head back to camp.

At camp, the deminers get some lunch and relax. A television was brought in for the 2014 World Cup and while I was there the teams watched highlights from Copa America football tournament in Chile.

All in a day’s (very good) work.

Many thanks to Tom Dibb and the entire team at HALO-Zimbabwe for letting me tag along. To learn more about HALO’s work in Zimbabwe, please visit their website.

Michael P. Moore

July 20, 2015

moe (at) landminesinafrica (dot) org

Mine Risk Education and Awareness in Zimbabwe

Posted: July 9, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: HALO Trust, landmines, mine risk education, Norwegian People's Aid, ZIMAC, Zimbabwe Leave a commentFor almost forty years, landmines have marked Zimbabwe’s borders. While some of those mines have been cleared, over a million remain. Communities on the Zimbabwe-Mozambique border have lived with these mines and each days thousands of people accept the risk and pass through the minefields to graze their livestock, tend their crops, collect water and even go to school. The fencing that marked the minefields were taken down long ago, the metal used for other purposes. All that remains are the mines.

With over 2,000 reported human casualties and 120,000 livestock casualties, people living in the border communities are aware of the mines and know their location. Despite the danger, they accept the risk.

Outside of the border regions, many Zimbabweans don’t know about landmines. Several individuals I spoke with believed that all of the mines had been cleared and in the interior of the country that is true. The only landmines left in Zimbabwe are along the border and there is little or no UXO contamination as is found in other countries. The localized nature of the landmine problem makes it easier to address, but also means that attention from the country as a whole has drifted.

Landmine clearance in Zimbabwe is progressing steadily at the moment, but could take another 30 years or more at the current levels of investment. With that timeline, a robust mine risk education program for the border communities, focusing on behavior change and reporting rather than awareness, is needed to minimize casualties until every mine is cleared.

In my opinion, more mine risk education is needed in Zimbabwe. The Zimbabwe Mine Action Center (ZIMAC) is able to provide mine risk education (MRE) thanks to support from the International Committee of the Red Cross. However ZIMAC only provides MRE in mine-affected communities on an “emergency” basis when there is an increase in the number of casualties or when ZIMAC receives a report of a mine or piece of unexploded ordnance (UXO) outside of the border region. ZIMAC does have an outreach program where they send representatives to regional agricultural fairs, but the number of beneficiaries is unclear. The humanitarian demining organizations, the HALO Trust and Norwegian Peoples Aid (NPA), have the capacity to provide MRE, but to do so would take staff away from landmine clearance and communities needed MRE can be hundreds of kilometers from current work sites.

One innovative response to this need is the proposed collaboration between the HALO Trust, the United States Embassy and the children’s literacy company, Happy Readers. Happy Readers is a Harare-based company which has produced a series of children’s books aimed at improving English literacy in Zimbabwe by providing entertaining and culturally-appropriate materials for primary schools. While Zimbabwe touts a 93% literacy rate, that figure is based upon the suspect belief that primary school enrollment constitutes functional literacy. Happy Readers’s research shows the true English literacy rate in rural Zimbabwean schools is much lower and leads to reduced professional opportunities later in life.

Using the HALO Trust’s expertise and financial support from the United States Embassy, Happy readers will produce a special volume of their children’s books focused on mine risk education. The book will feature characters introduced in other stories and have a special section at the end with information about how to report landmines and additional mine risk messages aimed at adults. In my conversations with Happy Readers and the HALO Trust, I understand that the proposed support from the Embassy may not cover the full costs of the volume, but Happy Readers are committed to the project all the same. I support this initiative and hope the international community can find a way to make up the balance of the costs.

A boy holds the picket from a Ploughshare mine. Each Ploughshare is protected by two buried landmines which he was lucky to avoid.

Beyond what Happy Readers is doing, funding should be secured to enable ZIMAC, HALO Trust or NPA to provide mine risk education to border communities. Again, the people living in the communities know about the risks, but they accept those risks. I saw many people using well-worn paths across the minefields, but HALO Trust showed me several places where they had found landmines just a meter or two from the paths so communities need to be informed about the risks in places they think are safe. Also, I saw a boy holding the stake from a Ploughshare mine and while all of the Ploughshare mines have been cleared, the landmine laid around the Ploughshares have not so people should be warned about metal scavenging in the minefields. Lastly, minefield markers need to be verified from time to time. Markers can be displaced by weather, animals or people and while doing so is a crime, there should be a system where the markers are checked and replaced if missing.

Zimbabwe Days 3 & 4, Minefields of Mukumbura

Posted: June 20, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: demining, HALO Trust, landmines, Zimbabwe 5 CommentsI spent the last two days as a guest of the fantastic HALO Trust, learning first-hand about their work on the northeastern border of Zimbabwe. The minefields here date back to the late 1970s during Zimbabwe’s liberation war and were laid by the Rhodesian government. In 1998 – 2000, Koch MineSafe, a commercial demining firm (which employed many of the same deminers currently working for HALO), cleared some of the landmines, but also left many still in the ground.

The Rhodesian government laid landmines in three rows: a Cordon Sanitaire minefield with barbed wire and buried anti-personnel mines closest to the border; three layers of Ploughshare (or Ploughshear), a directional fragmentation mine, similar to the Claymore, linked to overlapping tripwires, with each Ploughshare protected by two “keeper” landmines to prevent tampering; a reinforcement minefield consisting of two rows of anti-personnel landmines.

Koch cleared the Cordon Sanitaire landmines closest to the border and many of the Ploughshare landmines, but in most places left the reinforcement minefields (Koch’s contract covered clearance of the Cordon Sanitaire and two rows of Ploughshares). HALO is clearing all of the mines it finds, and during my visit I saw clearance of the reinforcement minefields and the third row of the Ploughshare minefield. The density of the minefields is such that HALO is clearing more than a thousand landmines a month (all anti-personnel mines), one of the highest clearance rates anywhere in the world.

On the left, Ploughshare mines; Top Center and Top Right, South African-made R2M2 mines; Bottom Center and Bottom Right, Portuguese-made MAPS mines.

Most of the Ploughshare mines detonated long ago, the only remnants are the stakes that held the mines and the keepers (Portuguese MAPS and either Italian-made VS50s [not pictured] or South African-made R2M2s). In the reinforcement minefield, all of the mines are the South African M2R2s, one of which I could see sitting on top of the ground, others are buried up to 20 centimeters.

Because the mines have been here for so long, the impacts on the local communities are staggering. In one village in HALO’s working area, more than 20 persons suffered landmine injuries resulting in amputations. In another community, 14 cattle were lost in a single year. At the local primary school, 66 children from Mozambique crossed the minefields twice every day to attend classes.

Map of HALO Trust’s working area (active sites in blue, cleared areas in green). The residents live in communities to the bottom left of the picture, separated from the minefields by the road. The Mukubura River, forming the border between Mozambique and Zimbabwe is marked in yellow.

The communities are aware of the minefields. Elders lived in the area when the mines were planted and many remembered the clearance work done by Koch. All have stories of friends, family members or livestock killed or injured by mines. But, the best farmland in the region cruelly lies between the minefield and the Mukumbura River and the water holes are in the same place. Many paths of various widths crisscross the minefields and while villagers felt safe on the paths, HALO found landmines just steps away.

Red circle marks were two landmines were found next to a heavily used track from the village to the watering holes by the river.

HALO has worked with the communities to identify the minefields, and has also provided assistance to many survivors. In addition to freeing up land for development and agriculture (many local headmen are eyeing the cleared fields for housing for their communities) and making the paths to and from the water holes safer, HALO has arranged for several amputees to receive new prosthetic limbs. For some survivors, these are the first limbs they have received in more than thirty years (or ever).

Two survivors flank July, one of HALO’s senior staff. Both survivors have received artificial limbs thanks to HALO’s intervention.

There is still much to be done. In addition to the HALO Trust, Norwegian People’s Aid is clearing minefields along the eastern border, around the city of Mutare, and the engineering division of Zimbabwe’s army is busy with the southeastern borders. Since 2013, the pace of clearance has increased immensely, but years more effort will be needed to clear the rest of the mines at the current levels of support.

The Month in Mines, July 2014

Posted: August 20, 2014 Filed under: Month in Mines | Tags: Africa, Angola, Egypt, HALO Trust, landmines, Mali, Mines Advisory Group, Mozambique, Nigeria, Norway, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, Uganda, Western Sahara, Zambia, Zimbabwe 2 CommentsIn case anyone was expecting a lull in mine action news following the Maputo Review Conference, July’s stories from the continent confirm that despite the positive news and outcomes from the Conference, landmines continue to take lives.

Nigeria

They must have known that they were in for a long, protracted struggle because the Nigerian Police Forces have developed and unveiled a new landmine-proof vehicle for use in combating insurgents (All Africa). Too late to #bringbackourgirls, but maybe the Nigerian police can prevent future kidnappings.

Tunisia

Three different landmine incidents occurred in the first week of July in the restive Mount Chaambi area along the Algerian border, killing at least four people and wounding six. In the first incident, four soldiers and two guardsmen were injured by a landmine when their vehicle drove over it near Kef (Tunisia Live). In the second incident, a civilian entered a closed military zone and died after stepping on a mine. There was no explanation for why the man entered the zone (AFP). In the third incident four soldiers, and maybe a civilian, were killed by a landmine, also near Kef (All Africa). Tunisian authorities blamed all casualties on Islamist forces who have been using Mount Chaambi as a base from which to threaten the government.

Western Sahara

Vice magazine and the War is Boring blog both profiled the Moroccan berm that splits the Western Sahara territory with 7 million landmines and has caused hundreds, if not thousands of casualties. Both pieces addressed the ongoing conflict and how Islamists have been trying to recruit members from the youths living in the refugee camps on the eastern side of the berm. Worth noting that Mohamed Abdelaziz, the President of Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) which is the government in-waiting for Western Sahara, has been in power since 1976, trailing only Cameroon’s Paul Biya as the longest-serving leader of a country.

Angola

Angolan authorities reported out on landmine clearance progress in Cuanza Sul, Benguela, Cunene and Moxico Provinces. Removing and destroying thousands of explosive remnants of war, the country continues to make slow progress towards becoming mine-free. In Cuanza Sul, almost 8 million square meters were cleared of mines over 18 years and now the focus is shifting to secondary and tertiary roads (All Africa). In Benguela, explosive items that had been stored for more than a year were finally destroyed. Prompt (certainly more prompt than seen in Benguela) destruction of stockpiled munitions is necessary to prevent accidentally discharges of munitions (All Africa). With the support of Mines Advisory Group, 1.5 million square meters in Moxico Province have already been cleared in 2014. Landmine clearance tasks have focused on access roads to allow free movement and the proposed high voltage lines for a future hydroelectric dam (All Africa). Cunene province’s agricultural outputs will be boosted by the clearing of farmlands and already half a million square meters have been cleared (All Africa).

Mozambique

The tensions between former rebel group RENAMO and the government of Mozambique continued in July which delayed landmine clearance in the Chibabava district of Sofala province. The government of Mozambique had hoped to finish all landmine clearance in 2014 and RENAMO’s actions threaten that timeline which means that Mozambicans may continue to live with the threat of landmines longer than was necessary (All Africa).

Zimbabwe

The director of the Zimbabwe Mine Action Centre (ZMAC), Col. Mkhululi Ncube testified before the Zimbabwean Senate’s Thematic Committee on Peace and Security, shortly after he participated in the Maputo Review Conference. Col. Ncube told the Committee that over 3,600 people have been killed or injured by landmines since 1980 and some 800,000 people have been economically affected by the continuing presence of landmines along the country’s borders. Landmines have hampered the tourism and agricultural industries in Zimbabwe as well as killing thousands of herd animals. Martin Rushwaya, representing the Ministry of Defence, said that as much as US $100 million may be needed to clear all of the landmines from the country.

In recent years most landmine injuries have been attributed to deliberate tampering with explosives by people trying to extract non-existent red mercury from the devices. In response ZMAC has been incorporating messages about red mercury in its mine risk education materials.

On the positive side, the minefield surrounding the Kariba Hydroelectric Power Station, the very first minefield laid in Zimbabwe when it was still a British colony, has been cleared and thousands of landmines have been cleared since work resumed in earnest in 2012 (All Africa; News Day; Zimbabwe Mail).

Sudan

The Higleg area of Sudan’s West Kordofan state has been declared free of landmines. Heglig was the site of fighting in 2011 between Sudan and South Sudan but has since been cleared of mines (Sudanese Online).

In North Darfur, heavy rains have exposed landmines laid by the government of Sudan according to one of the rebel groups, the Sudan Liberation Movement, Abdel Wahid El Nur. The landmines were spotted near Kutum town and were believed to be intended to “hamper movement of the Darfur resistance forces” (All Africa).

In response to the mine risk throughout the country, Sudan’s National Demining Center launched a mine risk education campaign in the five Darfur states and in Blue Nile state with the support of national and international organizations. The campaign will integrate mine risk messages into school curricula (GM Sudan).

Somalia

The Development Initiative has delivered mine risk education messages to over 170,000 Somalis and in the process provided job skills and education opportunities for the Somali staff working for the project (Devex).

Towards the end of the month, Mogadishu’s mayor narrowly avoided a possible assassination attempt when his vehicle drove over a landmine. The mayor and his security detail were protected from the blast by their vehicle but at least one passerby was killed and another injured by the blast (Sabahi).

Egypt

In late June, Stephen Beecroft was confirmed as the US Ambassador to Egypt. While Amb. Beecroft will undoubtedly have his hands full with issues related to the US relationship with Egypt and the assaults on democracy and human rights emanating from the current regime, we ask the Amb. Beecroft remember his time served in the State Department’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs where he was involved with landmine clearance. Egypt has the greatest number of landmines of any country in Africa, almost as many as all other African countries combined, and could use additional assistance to clear this lingering threat (All Gov).

Mali

The United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) has been active in Northern Mali for some time, responding to the threats of landmines and ERW which did not exist prior to the Islamist takeover of the region. Since March 2012, over one hundred civilians have been killed or injured by landmines and ERW, more than half of them children; almost 250 soldiers from the various national and international forces have been killed or injured since January 2013. UNMAS recently trained explosive ordnance disposal companies from Cambodia and Nepal who are serving in the United Nations peacekeeping force in Mali (MINUSMA). Two of the Cambodian peacekeepers were injured by an anti-personnel mine when their vehicle drove over the mine. Because it was an anti-personnel mine and not an anti-vehicle mine, the injuries were severe but not life-threatening. As the head of the Cambodian team in Mali put it, the driver’s “leg injury was not serious enough for it to be cut off and now he is in hospital in Mali” (Phnom Penh Post).

One point to make about the peacekeepers: Nepal and Cambodia, especially Cambodia, suffer from contamination from landmines and other ERW. Shouldn’t these trained deminers be working to clear their own countries of landmines before assisting others?

Uganda

Landmine survivor, advocate and director of the Uganda Landmine Survivors Association (ULSA), Margaret Arech Orech was selected by the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice at the University of San Diego as a 2014 Women PeaceMaker. As one of four such PeaceMakers, Ms. Orech will serve a three-month residency at the University and contribute to conversations about the role of women in international peacebuilding.

Zambia

Zambia has declared itself to be free of landmines, but the United Kingdom’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) recently updated its travel advice for Zambia saying “There is a risk of landmines in remote areas near the borders with Angola, Mozambique and [the Democratic Republic of Congo].” The FCO is not clear about whether or not it believes the landmines are in Zambian territory or if it is just warning travelers about the presence of landmines in the neighboring states along the border. If the FCO has evidence of landmines in Zambia, the FCO should share than knowledge so the government of Zambia can respond (Foreign and Commonwealth Office).

Because of Zambia’s experience in clearing its territory of landmines and ERW, the Foreign Minister, Harry Kalaba, offered his nation’s assistance to Vietnam to help Vietnam address its own landmine and ERW threat. The announcement came during Kalaba’s visit to Hanoi and is part of an effort to expand cooperation between the two countries (Vietnam News).

South Sudan (via South Africa)

South Africa’s parastatal company, Mechem, is one of the largest demining firms in Africa. In an article describing Mechem’s growing portfolio, the company’s general manager reported that Mechem provides bomb disposal services for the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) beginning July 1 and Mechem’s teams are destroying an average of a ton of ERW in Libya each month. However, Mechem also reports that the civil war in South Sudan has severely restricted activities there and Mechem is only able to do emergency work at the moment. Mechem also warned of the “strong possibility” of new landmine usage in South Sudan (Defence Web).

Norway

In a bit of irony, Norway, a leader in mine action around the world and a strong champion of the Mine Ban Treaty, twice evacuated a kindergarten in Karmøy in southwestern Norway after two landmines, presumably leftover from World War II, were discovered on the nearby beach in separate incidents in the same week. Both mines were quickly destroyed, but their presence serves as a reminder that landmines are a global issue (The Local).

Michael P. Moore

August 20, 2014

Moe (at) landminesinafrica (dot) org

Four Takeaways from the Maputo Conference on a Mine-Free World

Posted: July 9, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: 3rd Review Conference, demining, HALO Trust, landmines, Mine Ban Treaty, Norwegian People's Aid, Victim Assistance 1 CommentStates, advocates and survivors came together in the Mozambican capitol of Maputo to review the progress of the Mine Ban Treaty after 15 years of implementation and agree upon an agenda for the next five years. From June 23rd to the 27th nearly one thousand delegates participated in formal sessions and dozens of side events celebrating the Treaty’s accomplishments and preparing for the next phase of work. (Round-ups of each day’s activities, as reported in social media, can be found here: Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, and Day 4.) While there were entirely too many moments of note to try and summarize, from the United States’s announcement that it will no longer procure anti-personnel landmines (3rd Review Conference) to the continued confirmations from the host country of its desire to be mine-free by the end of the year (3rd Review Conference), there were four items that particularly stood out for me despite only observing the Conference from a distance of more than 8,000 miles away. These items include challenges from deminers, a defense of the use of landmines, and the continuing challenge of survivor assistance.

“Doing the Math on Clearance Rates”

Co-founder of the HALO Trust and current president of HALO-USA, Guy Willoughby, addressed the Conference’s attendees on Day 3 (The HALO Trust). With over 25 years of experience in humanitarian demining and over 7,000 employees employed in 17 countries clearing landmines, Mr. Willoughby challenged the attendees to “aspire to making landmines history” and reminded states that they had agreed to a ten-year deadline to clear all landmines. The HALO Trust’s forecasting shows that with modest increases in donor funding, all landmines could be cleared from Afghanistan, Angola, Armenia, Cambodia, Colombia, Georgia, Sri Lanka, Somalia and Zimbabwe by 2025. But, if mine action contributions decline, “Angola will take 28 more years to clear instead of ten… and Zimbabwe 48 more years.” Those delays would mean “thousands more human and livestock casualties, thousands of hectares left uncultivated.” The HALO Trust is widely respected within the mine action community and Mr. Willoughby’s intervention generated the momentum needed for the participants to agree upon 2025 as the goal for a landmine-free world.

“Persistent Failure”

Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) presented a report during a side event on June 26th which assessed the scope of the landmine clearance challenge that remained. NPA listed 40 countries, 24 of whom are party to the Mine Ban Treaty and 16 which are not, that are fully capable of clearing all known minefields by 2019. However, NPA’s report stated that “the primary obstacle to effective and efficient clearance of mined areas is not funding per se, as is sometimes alleged, much less the weather or difficult terrain, but lack of political will to get the job done. In particular, when we look at the Article 5 waifs and strays, such as Chad, Senegal, Turkey, and the United Kingdom (discussed below), it is has been lack of political will that is the major cause of persistent failure to implement Article 5, not the availability or otherwise of adequate funding.” The report goes further to critique the United Nations’ role in mine action saying the UN’s focus on capacity building of mine action centers was “a strategic mistake” with “petty squabbles about ‘who gets the overhead’ between UNDP, UNMAS, and UNOPS.” A better role for the UN would have been “to focus on generating political will at the higher levels of government, creating an enabling environment for mine action.” A further critique of the UN agencies was the fact that they “never sought to gather basic mine action data about contamination, progress in clearance, and victims.” The data problems are evident as mine action operators and mine action centers “are unable to disaggregate land release into cancelation of mined areas by non-technical survey, release by technical survey, or release by clearance, or even to distinguish battle area clearance from mine clearance.”

NPA’s report then lists the criteria for an effective mine action program that is fully able to address any existing landmine contamination. In NPA’s assessment: “The best performing mine action program in 2013 among 30 affected States Parties was Algeria, followed by Mauritania and Cambodia. The most improved mine action program in 2013 was Zimbabwe. The least performing mine action program in 2013 was Chad, slightly below Turkey and then, equally, Ethiopia, Senegal, and South Sudan.”

I love, love, love both of these interventions. The HALO Trust and NPA have decades of on-the-ground experience in landmine clearance and have born witness to what countries are capable of when those countries have the political will to act. Guy Willoughby challenged the donor community to step up and commit the necessary resources to deliver a landmine-free world and NPA called out those countries who have been negligent in their obligations. NPA’s report reflects what I have heard many people say in private conversations and I’m so happy to see them come out and say it out loud. Long overdue. On the flip side, here are the two things that I did not like so much:

“Harmonizing Military Necessity with Humanitarian Concerns”

I do not envy the Indian and Chinese delegations at the Maputo Conference which participated as observers since neither country has signed or acceded to the Mine Ban Treaty. The Indian delegation stated that the Mine Ban Treaty was unnecessary as “the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons provides the appropriate legal framework for harmonizing military necessity with humanitarian concerns” and defended the need for anti-personnel landmines as part of “the legitimate defence requirements of States, particularly those with long borders.” Despite its support for “a world free of the threat of landmines,” India’s “national security concerns oblige us currently to stay out of the Convention” (3rd Review Conference).

The Chinese delegation admitted to keeping “a very limited number” of anti-personnel landmines in its stockpile “for defence purpose.” These mines are compliant with the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons but absolutely banned by the Mine Ban Treaty. Also, in a challenge to the Mine Ban Treaty’s Article 5 which obligates States to clear known minefields within their territory, China advocated for “the principle of ‘user to clear’” to “accelerate the elimination of the landmine scourge.” The “user to clear” principle would relieve States of any obligation to protect their own citizens from landmines (3rd Review Conference).

By defending the use of landmines and reiterating their “legitimate” use, India and China continue to provide cover to states like Egypt, Morocco and Israel which remain outside the Mine Ban Treaty. As the Special Envoy for the Universalization of the Mine Ban Treaty said, the decision to ban landmines is not a military one, it is a humanitarian one. There is no balance between military utility and humanitarian costs when it comes to anti-personnel landmines; the humanitarian costs so far outweigh any possible military utility as to render the mines mere “weapons of cowards” as Pope Francis described them.

The “user to clear” principle is just wrong and let me offer two examples to show why. 1) In Zimbabwe there are over 1 million landmines that were laid by the Rhodesian government in the 1970s. Rhodesia has not existed since 1980 so who would be responsible for clearing its landmines if “user to clear” were the rule? 2) In current conflicts, most landmine users are rebel groups, not governments. Who would be responsible for clearing rebel-laid mines under “user to clear”?

“The Solemn Promise to Mine Victims”

In the Maputo Action Plan, the States Parties recommitted themselves to the “full, equal and effective participation of mine victims in society.” The Plan then goes on to say that each State Party with landmine victims “in areas under its jurisdiction or control… will do its utmost to assess the needs of mine victims… [and] will do its utmost to communicate to the States Parties… by April 30, 2015, time-bound and measurable objectives it seeks to achieve… that will contribute to the full, equal and effective participation of mine victims in society” (emphasis added) (Maputo Action Plan). Why, oh why, have States Parties not already conducted these needs assessments and why couldn’t States Parties come to Maputo prepared to discuss their objectives and activities to respond to these needs? Why will States Parties only do their “utmost” to meet these commitments? Why not have the commitments be binding? Because the commitments are not binding – a State can always say that it tried, but could not meet the deadline and still have fulfilled the obligation of the Action Plan – I am afraid that we are kicking the can down the road yet again. If we have made a “solemn promise to mine victims,” why can’t we keep it? How much longer will survivors trust the States when they make pledges that are not adhered to? The Maputo Action Plan says all of the right things, but in the end, there is nothing binding there on survivor assistance and we have once again let down this group that has led the charge for a mine-free world. I wish I was surprised and not just disappointed.

On the whole, the Conference was extremely positive, the Maputo Action Plan can be an aspirational document and hopefully the goal of a mine-free world in 2025 will be achieved. Let’s get to work.

Michael P. Moore

July 9, 2014

moe (at) landminesinafrica.org

Unacceptable Risk: The deliberate targeting of deminers

Posted: March 31, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Afghanistan, Danish Demining Group, demining, HALO Trust, Handicap International, landmines, Mozambique, Peacekeeping, Senegal, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, United Nations, War crimes, Yemen Leave a commentArticle 8.2(b)(iii) of the Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court (ICC) identified the act of “Intentionally directing attacks against personnel, installations, material, units or vehicles involved in a humanitarian assistance or peacekeeping mission in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, as long as they are entitled to the protection given to civilians or civilian objects under the international law of armed conflict” as a war crime for which the ICC would have jurisdiction (Rome Statute, pdf; German Law Journal). On this, the week we observe the annual International Day of Mine Awareness and Assistance (United Nations), it is important to recognize the fact that deminers not only face the very real risk of an accident in the line of their work, but deminers have also become a target of those who would wish to prevent peace and development. Too many deminers have been abducted, attacked, injured and killed in the line of duty. This must stop.

Last week, Afghan extremists targeted the guest house of the demining and development organization, Roots of Peace, and with bombs and guns, sought to end their commitment to turn “mines into vines.” In defiance, Roots of Peace “remains resolved to helping Afghan farmers nationwide to improve their incomes and create a stable economy” (Roots of Peace; Washington Post). We should follow the example of Roots of Peace and recommit to landmine clearance and mine risk education and call upon the international community to prosecute those who would hinder this important work.

What follows is a brief and by no means comprehensive list of attacks upon deminers over the last decade:

- 14-Mar-14 Afghanistan 1 adult, 1 child killed in attack on Roots of Peace guesthouse in Kabul.

- 21-Jan-14 Afghanistan 54 deminers from the HALO Trust abducted by Taliban near Herat; freed without injury by “police operation”

- 1-Nov-13 Mozambique Two deminers with Handical International shot by RENAMO members in attack on convoy traveling through Sofala Province.

- 2-Jul-13 Afghanistan Deminer working for Mine Clearance Planning Agency killed in Kandahar by NATO airstrike.

- 19-Jun-13 Somalia Two South Africans from Denel Mechem, contracted to do mine action in Somalia, were killed in an Al Shabaab attach on a United Nations compound in Mogadishu.

- 18-Jun-13 Yemen Six deminers and three soldiers were kidnapped by armed tribesmen in the southern province of Abyan.

- 9-May-13 Afghanistan 11 deminers with Mine Detection Center abducted in Nangarhar, local warlord “Sherwali” accused of crime.

- 3-May-13 Senegal Twelve deminers from South Africa’s Denel were abducted by MFDC rebels from the Cesar Badiate faction. All demining halted for six months. Three women were released after a couple of weeks; the nine men were released after two months.

- 23-Apr-13 Afghanistan In Meiwand, 9 deminers kidnapped by Taliban, held for one week and then released unharmed.

- 28-Apr-12 Sudan Two employees of the United Nations Mine Action Service and two employees of Denel Mechem were arrested by the Sudanese Army and accused of supporting the South Sudanese army. They were released, unharmed, six weeks later after negotiations involving former South African President Thabo Mbeki.

- 2-Apr-12 Afghanistan Three Deminers from HALO Trust kidnapped in Herat.

- 25-Oct-11 Somalia Three employees of the Danish Demining Group, a Dane, an American and a Somali, were abducted by “pirates” in northern Somalia while conducting mine risk education. The Somali was released almost immediately, but the Dane and American were held for three months for ransom. Both were freed by a US Special Forces operation that received White House attention.

- 9-Jul-11 Afghanistan 31 employees of the Demining Agency for Afghanistan abducted from Farah province. 4 deminers were killed (beheaded) before the other 27 were released after four or five days.

- 7-Jun-11 Afghanistan Deminer from the Mine Dog Detection Center killed in Logar province.

- 9-Dec-10 Afghanistan 18 employees from the Mine Detection Centre abducted from Khost province.

- 2-Dec-10 Afghanistan Seven deminers from the Organisation for Mine Clearance and Afghan Rehabilitation kidnapped from Nangarhar province and taken to Pakistan’s Khyber region.

- 10-Apr-10 Afghanistan Five employees of the Demining Agency for Afghanistan killed and another 13 injured in Kandahar province by a roadside bomb.

- 5-Jul-09 Afghanistan 16 deminers abducted as they traveled between Paktia and Khost provinces

- 19-Aug-08 Afghanistan In Gardez province, 11 demines and two drivers from the Mine Detection Centre abducted; seven released within 48 hours.

- 28-Jun-08 Somalia A Dane, a Swede and a Somali were kidnapped from the International Medical Corps compound in Hodur. The Dane and Swede were conducting a mine action training assignment on the United Nations behalf.

- 24-Mar-08 Afghanistan Five deminers from Afghan Technical Consulting killed, seven others injured in convoy ambush in Jawzjan province.

- 6-Sep-07 Afghanistan Thirteen deminers from Afghan Technical Consultants abducted; all released one week later with no reported casualties.

- 12-Jan-06 Sri Lanka Two deminers from the Danish Demining Group kidnapped by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in Jaffna Province.

- 11-Jan-05 Sudan Two deminers from the Swiss Foundation for Mine Action were killed by suspected members of the Lord’s Resistance Army

To absent friends.

Michael P. Moore

March 31, 2014

The Month in Mines, January 2014

Posted: February 10, 2014 Filed under: Month in Mines | Tags: Africa, Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo, HALO Trust, Handicap International, landmines, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, Zimbabwe 1 Comment2014 will mark the twentieth anniversary of Bill Clinton’s call for the “eventual elimination” of anti-personnel landmines. In an address to the United Nations General Assembly, Clinton said:

I am proposing a first step toward the eventual elimination of a less visible but still deadly threat: the world’s 85 million antipersonnel land mines, one for every 50 people on the face of the Earth. I ask all nations to join with us and conclude an agreement to reduce the number and availability of those mines. Ridding the world of those often hidden weapons will help to save the lives of tens of thousands of men and women and innocent children in the years to come (State Department).

To date, we have seen tremendous success in reducing the “number and availability” of anti-personnel landmines, but the “elimination” of landmines has been more “eventual” than I think anyone would have expected. But a new year is a time for new optimism; let’s see where 2014 takes us.

Somalia

A landmine targeting a Somali military vehicle traveling through the Yaqshid neighborhood north of Mogadishu killed a civilian woman and injured several others. A Somali soldier may also have been killed and other soldiers wounded, but no official confirmation of military casualties was made (Hiraan Online; All Africa). A few days later, a landmine detonated as an aid convoy passed on its way to Ifo 1 camp near the Dadaab refugee camp complex. Five Kenyan policemen were riding in the car that was struck and suffered minor injuries. This was the second such attack on an aid convoy in Dadaab in as many weeks (All Africa; All Africa; All Africa). On the Afgoye to Mogadishu road, two soldiers were killed and three others injured by a landmine (All Africa; Sabahi). In Galka’ayo town in the semi-autonomous region of Puntland, a landmine was placed under a bridge near the local hospital. When the mine was triggered, three people were killed and another seven injured (All Africa). And in Beledweyn town in central Somalia, a site of significant conflict, two landmine blasts occurred simultaneously. No casualties were reported but some witnesses believed that the person or persons who were planting the mines may have accidentally triggered them. The blasts were immediately followed by a security sweep which arrested dozens of young men suspected of complicity in the blasts (All Africa; All Africa).

The lone bright spot in Somalia comes from the semi-autonomous region of Somaliland. Since Somaliland is not recognized as an independent state, it cannot join the Mine Ban Treaty, but the government of the region has been working with Geneva Call to draft legislation that would mirror the Mine Ban Treaty and prohibit the use, transfer and stockpiling of landmines. The legislation is under consideration by Somaliland’s House of Representatives and may come to a full vote in the very near future (Somaliland Sun).

Angola

Angola’s government issued several end of year reports on landmine clearance work in 2013, province by province:

- In Huambo province, 3.1 million square meters of land were cleared (All Africa);

- In Bie Province, the HALO Trust cleared 129 landmines (All Africa);

- 3.23 million square meters of land were cleared in Lunda Sul province (All Africa);

- 180 kilometers of road linking Lunda Sul province with Lunda Norte province (All Africa);

- 240 sappers were trained between Lunda Norte province and Cunene Province (All Africa; All Africa); and

- 5.3 million square meters of land were cleared in Cunene province (Defence Web).

In total, more than 1,500 landmines and 100,000 explosive remnants of war (ERW) were cleared from Angola in 2013. The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, commended Angola on its work to “free the country from landmines.” There is lingering concern, however, despite the tremendous progress made in landmine clearance that the demining program is “hamstrung by lack of funding” and the work is being scaled back in various parts of the country (Defence Web; All Africa).

Sudan

Sudan, even after the partition that created South Sudan, has one of the worst landmine contamination problems in Africa. Since the conclusion of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005, Sudan has made significant progress to clear its known minefields with some 385 minefields consisting of 42.6 million square meters of land cleared since 2011. Local organizations like JASMAR and Friends of Development Organization have been working on mine risk education in addition to clearance and now the local communities of Sudan can report any discovered ERW (UNOCHA). As a result of these efforts, in January the government of Sudan declared several areas of East Sudan, including Togan, and that Kassala state is expected to be landmine-free in 2014. The landmines and ERW is these areas date back to World War II and continued through 2007. The states of Kassala, Red Sea and Gedaref have some 545 landmine survivors and the government has recognized landmines as “the main obstacle to comprehensive development, reconstruction, and voluntary return to affected areas.” Another 500 landmine survivors have been registered elsewhere in Sudan but efforts for survivor assistance were not highlighted in the recent announcements about landmine clearance (All Africa; All Africa).

Tunisia

Tunisian authorities arrested three persons, a “terrorist” and two others in the Kasserine region, and seized three landmines. Over the last several months, several landmines have detonated around Kasserine and nearby Mount Chaambi were Islamist fighters have been suspected of hiding (All Africa).

Zimbabwe

As landmine clearance expands in Zimbabwe with the support of the HALO Trust and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), mine risk education programs for school children have also begun. Some 9,300 students who live near the border minefields of Crooks Corner received mine risk education to learn how to identify and avoid anti-personnel landmines (Relief Web).

A year ago, six people were killed when a traditional healer tried to extract red mercury from what was later identified as an anti-vehicle landmine. Three houses were completely destroyed and a dozen others damaged. To date, the survivors of the blast continue to struggle in temporary housing (All Africa). I bring up this story because a soldier stationed at the Zimbabwe Nation Army ammunitions depot in Mashonaland West Province was arrested and convicted in January for conspiring to sell landmines and grenades in order to extract the red mercury they believed was inside (Bulawayo 24). So let’s all repeat:

- There is no such thing as red mercury.

- Tampering with landmines is extremely dangerous.

- Enough people are killed and injured by landmines.

Nigeria

The Boko Haram conflict in northern Nigeria is one of the bloodiest in Africa. Characterized as an insurgency or coordinated series of terrorist attacks, I think it’s rapidly developing into a civil war. I am skeptical of most reporting on the Boko Haram conflict, but there is the possibility that the group has started to use victim-activated landmines in addition to other improvised explosive devices. According to one report, more than 50 people were killed in Borno State and 300 houses destroyed on the last weekend of January. A security source said “The [Boko Haram] attackers used several improvised explosive devices and planted several improvised explosive devices around the village as they were leaving. Two improved explosives went off this morning, narrowly missing our security personnel going there to evacuate corpses.” Referring to the planted bombs as “landmines,” as the paper, “Leadership,” has done may be an accurate portrayal of Boko Haram’s devices. The fact that the bombs went off many hours after the attack and appear to have been used as booby-traps for persons clearing the bodies of those killed is suggestive of a victim-activated device (All Africa).

South Sudan

The majority of the coverage of South Sudan lately has been rightly focused on the half million people displaced and 10,000 killed in violence between factions loyal to President Salva Kiir and ousted Vice President Riek Machar. While a Cessation of Hostilities agreement was signed by the two sides, violence continues as does displacement both within South Sudan and in refugee camps in neighboring countries. Displaced persons are at a high risk of landmine injury due to the fact that they are traveling through unfamiliar territory, quickly and with little or no support from official sources. That risk was made evident when two people were killed and another 14 injured as the Land Cruiser they were riding in drove over a landmine in Upper Nile State. The Land Cruiser was being used a form of public transportation and served the needs of people who were displaced (Radio Tamazuj). I am certain there have been other landmine injuries during the weeks of violence, but this was the only confirmable report I have seen.

Democratic Republic of Congo

Handicap International (HI) has launched a new demining program in Orientale and Maniema provinces in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Some 30,000 square meters of land near the city of Kisangani will be cleared using a combination of mechanical methods and manual methods. Between a 36-ton MineWolf and a team of mine-sniffing German Shepherd dogs, HI’s deminers in DRC hope to make rapid progress. Similar combinations of techniques have cleared more than 12 million square meters of land in Mozambique (Handicap International).

Mozambique

Speaking of Mozambique, the Belgian organization APOPO will be deploying a “small army” of its specially trained rats to help the country meet its mine clearance deadline of December 31, 2014. In a perfect description of humanitarian demining, APOPO’s Mozambique program manager, Tess Tewelde, said, “The target is not the number of landmines, rather it is to clear the contaminated area and give back to the people. Whether [landmines] are few or many, the threat is the same” (The Guardian).

Mali

Five United Nations peacekeepers were slightly injured when their vehicle ran over a landmine some 20 miles from the northern town of Kidal. Kidal had been held by Islamists prior to the French military’s intervention in the country and still has some rebel elements active in the region. The identity of the peacekeepers is unknown, but most of the troops are from other African countries with some French and Chinese soldiers participating in the UN Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) (The Telegraph).

Michael P. Moore

February 10, 2014

In Defense of the HALO Trust

Posted: January 23, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: civil society, HALO Trust, landmines, Media 3 CommentsOver the last two and half years, I have relayed dozens of stories about the good work the HALO (Hazardous Area, Life-Support Organization) Trust (www.halotrust.org) does in Africa. HALO has cleared thousands of landmines from Angola, Mozambique and Somalia, launched a new project in Zimbabwe and returned huge swaths of land to their communities to allow people affected by war to re-start their lives. Unfortunately, other outlets choose not to cover these stories which are the results of the efforts of thousands of men and women working around the world. Instead, two stories have been making the rounds in the last week, one of which has had a positive resolution, the other not so much, not yet. On January 21st, more than 60 of HALO’s employees, all Afghan nationals, were kidnapped by armed men near the city of Herat. After a few hours, all of the deminers were released thanks to the efforts of Afghanistan’s police forces (Washington Post). A couple of days before the kidnapping, stories appeared in the British papers the Telegraph and the Daily Mail describing the annual salary and benefits paid to HALO’s chief executive and co-founder, Guy Willoughby. The stories had a breathless tone as they described the fact that HALO pays for Willoghby’s four children to attend private schools where the annual tuition costs are US $45,000 or more. While I am not as scandalized by these stories as the Daily Mail or Telegraph would like me to be because I am admirer of HALO’s landmine clearance work, I do think the stories raise two important questions that are applicable to the entire not-for-profit community: 1) Is the HALO Trust’s chief executive (or any organization’s chief executive) overpaid? (No.); and 2) Did the HALO Trust’s board of directors do its job as a not-for-profit organization’s board? (Maybe.)

First, it’s important to remember that the Daily Mail is a celebrity-driven tabloid whose coverage of the story always includes references to the celebrities associated with HALO including Princess Diana, Prince Harry and Angelina Jolie. Were it not for these celebrities and their ties to HALO (and the opportunity to include photos of them with the story), the Daily Mail would probably not have covered this story. The Telegraph is not innocent in pursuing the celebrity angle either, naming Prince Harry and Angelina Jolie in their story’s headline. Second, I’ve covered questions of waste and fraud at not-for-profit organizations elsewhere on this blog and I think these particular stories represent an incomplete understanding of how the not-for-profit industry operates and exploits that absence of understanding to sensationalize what is a rather mundane question of executive compensation. Third, the HALO Trust clears landmines from countries like Afghanistan, Mozambique, Sudan, Sri Lanka; the importance of that work should never be lost in these organizational matters. So, let’s get into the substance at hand.

Question 1: Is the HALO Trust’s chief executive overpaid? Short answer: no. Like most chief executives at not-for-profit organizations (or charities), Mr. Willoughby’s primary responsibility to the organization is to raise money for the work of the organization and by any measure, he’s been pretty successful. In FY2013, HALO recorded income of more than US $43 million and employed between 5,000 and 8,000 people in more than a dozen countries around the world. Founded in 1988, HALO is celebrating its 25th anniversary and Willoughby has said in the past that he believes a mine-free world is possible in the next ten to twenty-five years. HALO has confirmed that it offers a “school fees scheme for senior staff with more than seven years’ service, and children from the age of 10 to 18 are eligible;” such benefits are considered taxable income and part of the employees’ salary (Third Sector). HALO defended its decision to offer such a benefit to Willoughby and a couple of other staff as being in line with benefits packages offered by United Nations organizations and other large development organizations for whom payment of school fees for expatriate staff is common.

Guy Willoughby’s salary is set by the HALO Trust’s board of directors and Willoughby is accountable to the board. Therefore, the salary HALO pays Willoughby is based upon the value the board places upon his work, which is very high and based upon the results he has achieved. Think about this way, if Willoughby were not successful at raising money and raising awareness, the opportunity for this story would not exist. Before the HALO Trust was founded, the concept of humanitarian demining barely existed. Willoughby has helped to shape the industry he is now a leader of. His fundraising success, work that has paid for clearance of thousands of landmines and enabled hundreds of communities to rebuild after conflict, makes him valuable to the organization as a leader and spokesperson. Willoughby’s ability to recruit celebrities, like Diana, Harry and Angelina, to help him spread the word about landmines is what makes him valuable to the organization. Without Willoughby, there would be no HALO Trust and no story for the Telegraph or Daily Mail to cover. Which brings us to the board.

Question 2: Did the board of directors of the HALO Trust do its job? Short answer: maybe. The board of directors for a not-for-profit organization or charity is tasked with oversight of the organization on the public’s behalf. As the co-founder of the HALO Trust, one of Willoughby’s responsibilities has been to recruit a board of directors to oversee the organization. And as the chief executive, Willoughby is accountable to the board. This is the problem. Willoughby is accountable to people he personally recruited to serve on the board; many of the board members joined the board because they believed in what Willoughby had created and wanted to support it. In situations like this, where a person starts and runs an organization, the board of that organization is often in the difficult situation of managing what it sees as the greatest asset of the organization: the founder. In that situation, can the board objectively evaluate the chief executive’s performance? Some boards can and some can’t. It all depends on the people who serve on the board and how they view their role. Or asked another way: is their role to support the founder’s vision or support the founder, him or herself? It can be hard to separate the person from the vision and it is not a task I envy of anyone.

Also, it is important to ask what is the correct motivation for the chief executive. In the for-profit world, chief executives are believed to be best motivated by financial compensation in the form of high salaries and stock options or benefits. If a chief executive felt he or she would receive a better financial package elsewhere, the executive would be tempted to leave. This assumes that chief executive’s skills are easily transportable and applicable to different companies. In the not-for-profit world, we believe (hope?) all employees are motivated by the mission of the organization and not by financial rewards. Sure, we all want to be able to provide for ourselves and our families, but the opportunity to support the organization’s mission alleviates the need for using money as the sole incentive. This leads to the question: what would it take to lure Guy Willoughby away from the HALO Trust? I don’t know, but if HALO’s board doesn’t, then it needs to find out.

Question 3: Does it matter? No. The HALO Trust, as evidenced by the experience of its deminers in Afghanistan, works in some of the most difficult conditions doing work that is necessary and life-saving. With thousands of men and women in the field clearing landmines to help rebuild countries torn apart by conflict, the real story about HALO should be about the lives it saves. If only it could get as much coverage for that. The not-for-profit community does far more good than it gets credit for and the sensationalization of stories about the industry is reckless and irresponsible. Could we be better? Yes, but there are safeguards in place – in the form of boards of directors, audits, financial reporting and internal controls – and they work far more often then the authors of stories like the Daily Mail’s would have you believe.

Michael P. Moore

January 23, 2014